Everything you read here may soon be stolen.

Island is the work of writers who build their craft over years. They miss opportunities for paid employment, for fun, for time with family and friends, so they can slowly, slowly, slowly get better. They apply themselves for days, weeks, months to a piece of writing until it’s good enough to submit. And if it’s selected for publication, they spend many more hours perfecting their work with the help of Island’s editors.

At Island, we are dedicated to paying writers. This payment is the result of a great deal of careful work behind the scenes – consideration of budgets, contracts, funding sources – all with the aim of making sure that writers get paid fairly and on time. And yet, corporations like Meta, full of well-remunerated employees turning over millions of dollars in profit, seemingly cannot find the money in their budgets or the time in their day to develop a way to pay writers for their work; instead, they simply take it and use it to train artificial intelligence. Governments, meanwhile, seem willing to shrug their shoulders and let them off the hook.

Australia has copyright laws. They should protect the work of writers. If you enjoy what you read in this magazine, if you value what writers do, please contact your MP and tell them so.

— Jane Rawson, Editorial Manager

The poems in this issue arise both out of the everyday and the urgent. The strange wonders of driving ‘60 ks over’ (Aranjuez), the ‘curt contralto’ of a voice message prompt (Wright) or the ‘plastic dark’ outside a cinema (Cheng) all come alive here. Cartwright’s ‘Widow’s sestina’ strips a house down to its foundations, cannily using the repetitions of the form to enact a dismantling. Drummond’s ‘Ghost glosa’ is unsettled, attuned to ‘the shimmer/starburst, seed-puff, breath’. Mitchell’s ‘discarded remnants’ form ‘a monument’, and for Crutchfield the home becomes a space of hazard. Other poems reveal that the everyday and the urgent are one and the same, as when the weather turns. Beveridge writes of ‘Raptorial winds’, while Loveday states ‘the word apocalyptic loosens’ amid torrent. Meanwhile, illness transforms the everyday: Collins recounts the course of radiation, while Sometimes summons astronomy – the ‘body become nebulae’ – in treatment. Meanwhile van Neerven takes us to the semantic brink as all their human actions – mundane, extraordinary – transform to become fishlike.

— Kate Middleton, Poetry Editor

The fiction in this issue seems a sustained exploration of the theme of being beset, of the vulnerable being targeted by outside forces. It’s easy to imagine why these ideas are on writers’ minds, and the presence, wit, balance and urgency of their voices reform and reimagine them in surprising ways. In Alex Goodfellow’s ‘A quiet day’, a domestic worker looks after surfaces while, underneath, crisis develops. In Gabrielle Lis’s ‘I was once my mother’s darling’, a deity grapples with meaning in a changing world, while in ‘Jayvon’, James Bradley slowly subverts a coming-of-age story. Questions of futility and giving up are weighed in Hei Gou’s ‘The ascent’ and, in ‘The spring cycle’ by Cloe Anlezark, intruders conspire about a child’s intricate world.

— Kate Kruimink, Fiction Editor

It’s perhaps not surprising (and it’s certainly welcome), that after decades of tackling the ‘Australian Identity’ in nonfiction writing, we still haven’t found consensus. Happily, writers continue to offer a range of deeply personal takes on the subject. Some of those takes can be found in this issue. Jen Saunders looks at local histories, museum cultures, and patterns of archival absence in her absorbing essay ‘Calibrating’. In ‘Richmond Green’, Isabel Greenslade takes a job in an Australian-themed pub and attempts, from a distance, to define her own Australian identity. Alistair Kitchen writes on remote rainforest upbringings, rural masculinities, and settler narratives of the Australian landscape in his ranging essay ‘Out the Springbrook Road’. In ‘Jailbait’, Daisy McClelland recalls her introduction to the world of professional classical music, and examines the vulnerable position of young, emerging musicians. And finally, in a stunning work of endurance and deep time, Palawa writer and activist Krystelle Jordan offers a geological creation story of Lutruwita with her essay ‘Born of stone’.

— Keely Jobe, Nonfiction Editor

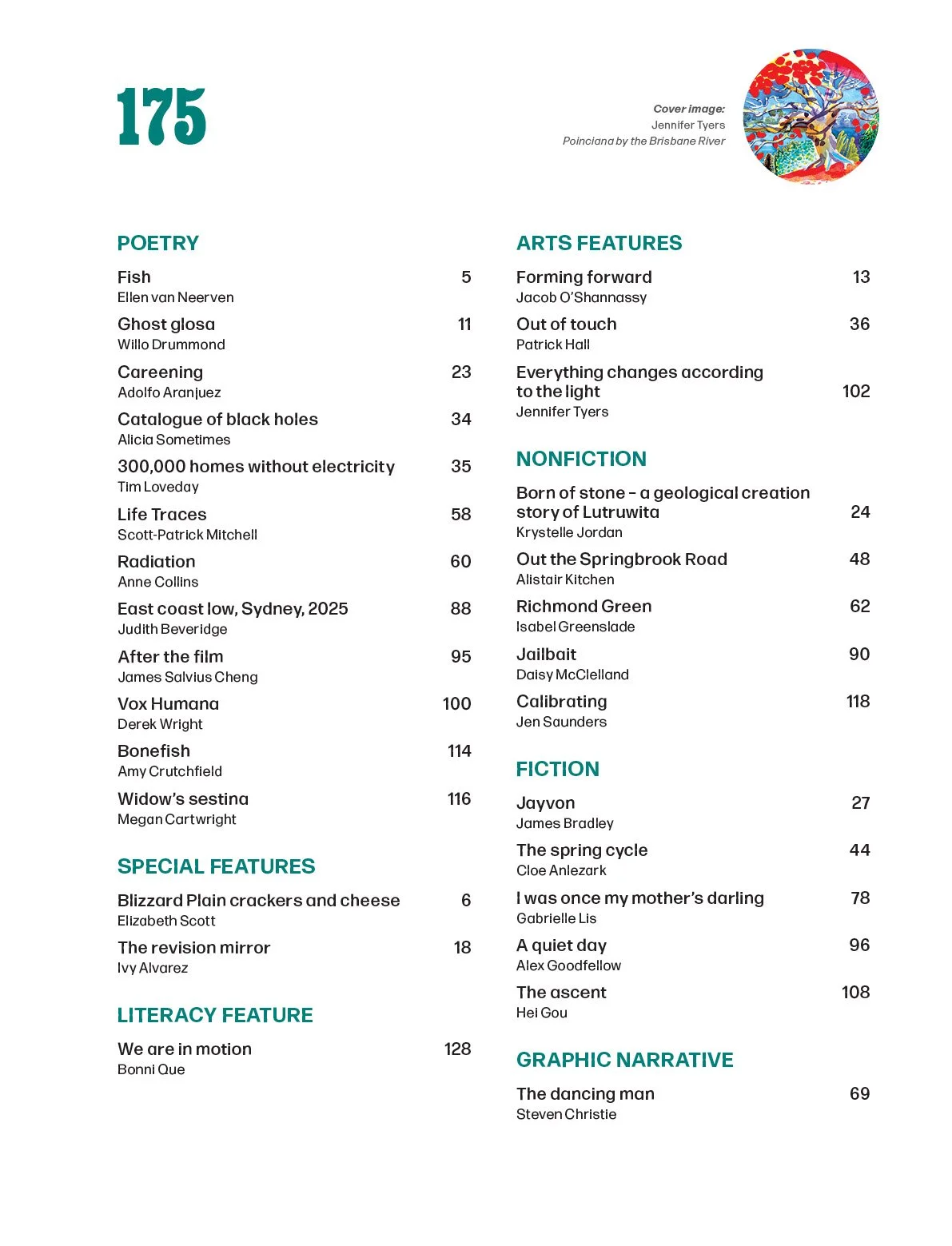

In this issue there is a diverse dialogue between the works within the arts features, yet there are definite ties between them of connectivity, awe and wonder. Jennifer Tyers’s vibrant work is this issue’s striking cover art and it translates well the exuberance and complexity of the content featured within. Tyers’s varied and captivating works embrace the full spectrum of the landscapes she studies with such an intrinsic approach. They feel as though she has transferred the electric splendour of these lush wild places directly into her works. Jacob O’Shannassy has a way of developing scenes that feel like fleeting snapshots from other curious and abundant worlds. There is a sense of rawness, of being stripped back and starting anew. O’Shannassy’s paintings and drawings are freeform and are as rich in reference as they are in the use of colour. For a long time, Patrick Hall’s wondrous works have left me deeply affected. Hall’s unique interpretation of life and the deftness shown through the creation of his extensive works are quite extraordinary. Artists such as Patrick Hall remind us of our glorious and conflicted humanity.

— Tamzen Brewster, Arts Features Editor

Some of us are too proud to admit the truth: we’re suckers for the well-crafted rom-com. We all sit on the bus with our secret ‘trash’ stuffed inside the dust jacket of a Peter Carey book we’ve not even heard of. We gush as the characters navigate their first encounter, their stumbles, hopes, projections, desire, mistakes, the longing for touch, the yearning. Steven Christie has several strengths in graphic narrative creation but let’s hone in on two that he’s brought to this issue of Island that excite me: his economical and captivating script-writing that comes together with a rush, and his unapologetic delight in his characters’ weirdness. ‘The dancing man’ is an oddly shaped diamond and I propose to you, the broader romance-connoisseur community, that the finest examples of this most-excellent genre are the ones that focus on two individual fragments trying their best to connect with someone whose weirdness is compatible with their own.

— Joshua Santospirito, Graphic Narratives Editor