Infrared – by Ryan Delaney

ISLAND | ONLINE ONLYEmily scans the bush for signs of life. She can spot Ben and Gary in the distance – their lurid, wattle-coloured jumpsuits making them stand out amongst the burnt gum trees. Their eyes will be peeled for fresh droppings, scratches on black trunks and animal tracks imprinted in the ash. As she watches the men solemnly comb the scorched earth, Emily wonders if there is really a difference anymore between a forensic and environmental scientist.

On the surface, the land appears to be healing. Bright pink and green epicormic shoots have burst through black bark and are beginning to flower. Other native pyrophites – such as blackboys, bottlebrush and banksia – are not only surviving but flourishing in this post-fire landscape, their hardy seeds split open by the extreme heat. It is these images of regrowth and the regenerative power of the Australian bush that journalists are currently foregrounding. Emily doesn’t blame them. People need hope in times of crisis – no matter how naïve or distorted.

Every morning and night, from the safety of their Waterloo apartment, Emily and her partner, Andrew, had followed the spread of the fire. Thanks to IVF, Emily was in her first trimester after 18 months of trying. But as she watched the harrowing footage, Emily found herself questioning, once again, the act of birthing a child into a world plagued by fires and floods. It was something she and Andrew had discussed in detail before she decided to go off the pill. Emily had eventually come to the realisation that the Earth didn’t really give a shit if she gave birth or not – and that thinking her procreation was somehow significant was the same individualist thinking that is fuelling ecological collapse.

“Emily had eventually come to the realisation that the Earth didn’t really give a shit if she gave birth or not – and that thinking her procreation was somehow significant was the same individualist thinking that is fuelling ecological collapse.”

A long Cooee echoes through the bush. Emily can no longer see her colleagues but there is no mistaking the sound for birdsong as the land is eerily quiet. She sets off in the direction of the call – her stomach stirring with anticipation.

On the drive to the national park, the trio passed through multiple fire-devastated townships. Emily was surprised to spot the hollow, skeletal structures of new homes already popping up amongst the rubble. Many families seemed to be not so much rebuilding their past lives as preparing for an uncertain future, opting for coated bushfire-resistant steel frames this time around. To Emily, the bright blue structures stood out from the black bush like holograms – intangible projections of light that could glitch, flicker and disappear in an instant.

Emily locates Ben and Gary back at the LandCruiser.

‘Find anything?’ she asks.

‘Nah mate,’ sighs Gary. He twists the lid off his thermos, takes a long scull then pours some water over his bald head. ‘The cherry picker will be here soon though – just in case.’

Emily doesn’t know much about Gary except that he’s been a local firefighter and park ranger for over thirty years. Earlier in the day, as they drove through a severely burnt valley, Gary told her that he hadn’t lost anything in the recent fires – that he had been one of the lucky ones. She looks at him now – with his sunken eyes and vacant gaze – and wonders if that’s true.

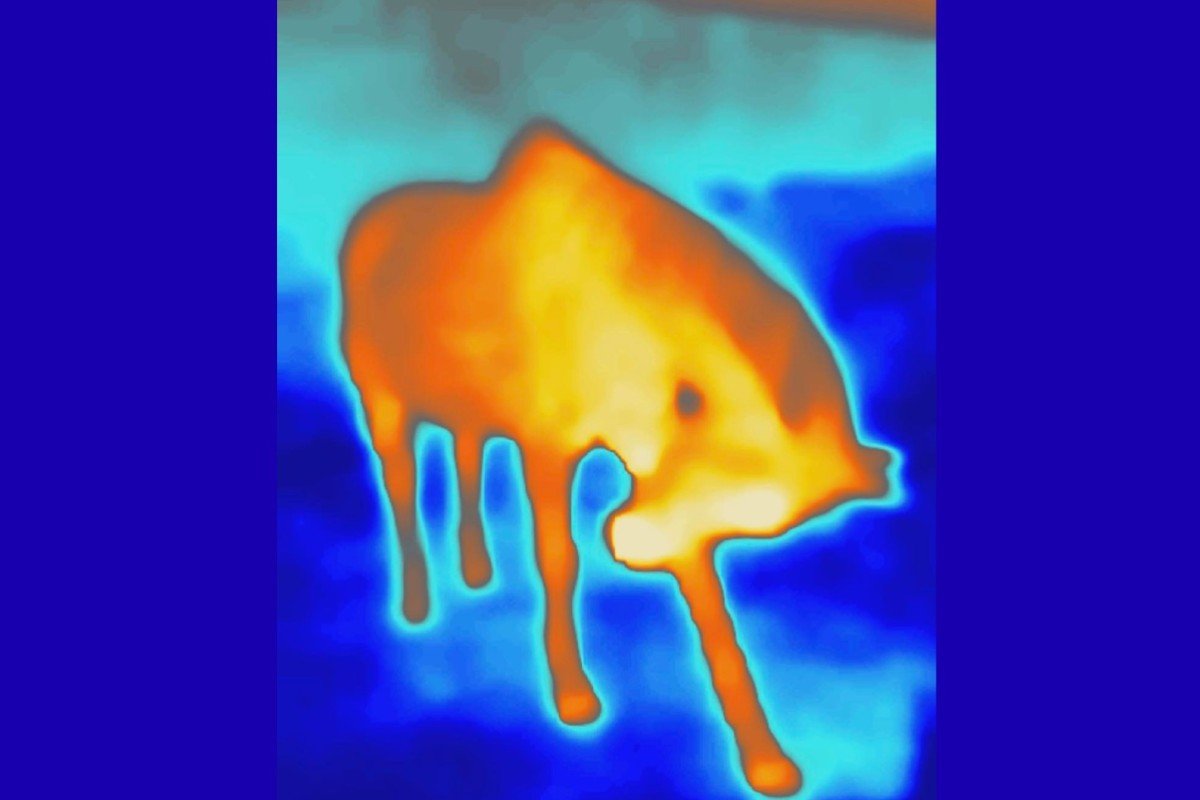

Ben takes the thermal tracking drone out of its hard case, switches it on and lets the tiny whirring machine hover steadily a metre or two above the ground. The drone’s single eye tilts and turns on its axis like a curious animal before locking directly on Emily. She stares back, unsettled by the bizarre confluence of the mechanical and the creaturely.

The drone’s thermal vision is similar to that of mosquitoes, vampire bats, snakes and goldfish. Like many animals, it can see heat as light, and can locate warm-blooded life in a barren landscape. Emily realises that she too would have become a nocturnal being with thermal-like capacities – a possessive, milk-laden creature seeking out her warm bundle of flesh in the dead of night.

‘Up and away,’ says Ben, and he sends the drone vertically up towards the sky. For two years now, Ben has been researching the burgeoning role of thermography in environmental conservation. As his PhD supervisor, Emily has come to realise the vast potential of the technology. She’s read about thermographic cameras tracing the changing nocturnal habits of fruit bats in Papua New Guinea, revealing how hummingbirds shed their heat in flight, and helping to help keep rhinos and elephants safe from poachers in South Africa. But Ben has recently shared reports that suggest that the poachers have been using the technology to hunt the critically endangered animals. It’s strange, Emily thinks: how one technology can be used to both protect and to destroy.

“It’s strange, Emily thinks: how one technology can be used to both protect and to destroy.”

The thermal footage is being streamed to a large monitor in the boot of the Land Cruiser. Gary appears indifferent, but Emily is astonished by the fluorescent colours on the screen – how a seemingly dead landscape glows with bright energy.

The animals of this land glow too – bilbies, bandicoots, Tassie devils, flying foxes, wombats, microbats. For weeks after she first saw images of a long-dead Tasmanian platypus lit up in fluorescent greens and blues under ultraviolet light, Emily found herself returning again and again to the mystery of the dead-yet-glowing creature. It made her think about how, perhaps, death is not so much an end as it is a transferral of heat and light.

‘Let’s try somewhere else,’ suggests Ben, and he skilfully guides the drone out of the bush and into a small clearing.

‘Eagle!’ yells Gary, and there is a flash of luminous wings and claws before the drone tumbles through the air and lands hard on the ashen ground. The screen is all static.

‘Fuck,’ mutters Ben, mashing the buttons on his remote control.

‘Must’ve been a very hungry bird,’ says Gary.

Ben activates the inbuilt GPS tracker and leads the group back into the bush. Emily and Gary follow at a distance – stopping regularly to gaze up into the flowering branches.

‘You know you’re like super fertile right now?’ Andrew had said, one humid evening in January. They were eating take-away on the balcony – their outdoor table covered in a thin layer of ash.

Emily ignored the question and stared out into the balmy night. With each day, she had grown more accepting of her body – become increasingly comfortable with its limitations. Like many of her colleagues, Emily dealt with grief by burrowing deeper into her work. The fires were still burning out of control, and Emily felt her tiny sorrow become consumed by a sadness much greater – hungrier.

‘This isn’t just your decision,’ Andrew said in bed that night, before he switched off his light and turned his back on Emily.

Ben eventually disappears over a ridge. He has led the trio right into the centre of the national park. All around, burnt gum trees loom. Their fire-smooth limbs creak and groan in the breeze.

Gary sits down on a fallen trunk and puts his hands across his chest. He’s rocking back and forth – sucking air deep into his lungs.

Emily approaches him like she would a wild animal – slowly and with an assured softness.

‘It’s okay, it’s okay,’ Emily repeats, as she sits next to him and gently places a hand on his shoulder.

‘They’re gone,’ he gasps. ‘They’re all gone.’ ▼

*This bushfire story was workshopped with Alice Bishop - author of A Constant Hum (2019).

Image: infrared image supplied by the author

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.