Phantom Menace Hours – by Victoria Manifold

ISLAND | ONLINE ONLYIt’s real Phantom Menace hours down at the motel. I’m waiting for Adam. We’re having an affair but haven’t consummated it yet. I’m vaguely worried that if we have sex it’ll be terrible, ‘not because of me,’ I’d told him, ‘I’m really good at it.’ And it’s true. I have a great track record with lots of positive feedback.

When Adam arrives his face is bleeding, as is typical of the times in which we live. Blood on his forehead, cheek, a small part of his chin. We press our faces together. He takes me in his arms, stoops to nuzzle my neck.

‘Oh, Greta, Greta, Greta,’ he whispers to me.

‘Who’s Greta?’ I ask.

‘She’s an actress I like, from that thing on TV.’

‘Oh,’ I say.

‘Do you mind? I can say Virginia if you like?’

‘No, Greta is fine.’

‘Oh, Greta, Greta, Greta,’ he begins again.

It doesn’t matter what Adam calls me, that’s part of the fantasy. I want Adam to hurt me – not to choke or slap me, though of course I do want that too – but some deeper humiliation. I walk into a bar and he ignores me because he’s talking to a much prettier girl; or he’s only initiated an affair with me as a joke; or he’s keeping our affair secret, not out of respect but because of embarrassment.

Sitting in my beautiful house, looking at my lovely things – ceramics, cushions and suchlike – I imagine Adam walking in just to laugh at them for reasons that I can’t quite discern but that probably have something to do with my age and upbringing. I want him to rub my face in my folly, to sneer and call my expensive shoes tasteless, my handmade stationery gauche. To see my husband and say something like ‘oh, you would be married to someone like that.’

Adam and I met at work, where I’m a regional manager and he’s a pathetic waste of space. I’d found him crying in the toilets because his brother and one of his parents —his mother or his father – had died that morning. In the toilet cubicle I’d held him in my arms. I’d never felt so close to a person. Before I knew what was happening I’d become obsessed with the whorls of his fingerprints, the trench of his clavicle.

Adam makes it easy for me to forget the suffocating affections of my husband, his soft kisses and love notes, his concern for my wellbeing. We sit together on the edge of the bed, watching TV, our hands touching. I can barely remember the buzzing irritants that were my children, their milk smells and endless needs. When Adam parts his lips and I see the tip of his tongue, wet and dark against his teeth, I forget the sounds they made as I tore up their Pokémon cards.

Outside the motel, everyone is tired and sick, everyone has been radicalised one way or another. Vague symptoms have plagued us since early spring and now it’s almost autumn. It started with fatigue and dizziness, followed by sudden loud noises in our left ears and a low hum in our right, before a crushing pressure began around the sides of our heads, stretching across our cheeks on to the bridge of our noses. Doctors have been so baffled they’ve refused to see patients, but patients simply wait outside their offices begging for consultation, for diagnosis. On the first day of summer the doctors threw up their hands and said: ‘it’s probably a thyroid condition, it’s probably nervous exhaustion, it’s probably a physical manifestation of a mild mental illness.’ A loud cheer rang out. The prescription medications they gave us did not improve our condition, but being able to name our sickness made it bearable, at least.

“On the first day of summer the doctors threw up their hands and said: ‘it’s probably a thyroid condition, it’s probably nervous exhaustion, it’s probably a physical manifestation of a mild mental illness.’ A loud cheer rang out. The prescription medications they gave us did not improve our condition, but being able to name our sickness made it bearable, at least.”

On the second day of summer, the usually highly dependable bus service became erratic. Local schools were placed on special measures as marks plummeted and staff rooms became sites of mass weeping, as the special creepy-crawly gardens that edged the playgrounds turned to dust and blew away. The end of term came sooner than planned.

Soon the fields and scrub that edged our busy market town were burning constantly and filling the air with thick brown smoke. It hadn’t rained all year and the mayor – a usually astute and well-dressed man – made a series of unwise decisions regarding Christmas illuminations that only served to worsen the situation. On the third and fourth days of summer we learned that certain political machinations, ordinarily hidden from people like us, had disastrously failed. Quietly, we feared the consequences.

“On the third and fourth days of summer we learned that certain political machinations, ordinarily hidden from people like us, had disastrously failed. Quietly, we feared the consequences.”

‘I love this film,’ Adam says. I look at his eager face in profile and press the mute button on the remote. I run my fingers through his hair, smell the delicious musk of his neck. But still I catch Adam trying to read Mace Windu’s lips, still I see his eyes following the lightsabers in the darkness. I rub my hand on his thigh, moving closer to the lump his dick makes in his jeans. I get up, standing between him and the television so he can’t see the action. I unzip my dress with an unnecessary wiggle and a little bit of lip licking. Adam seems aroused by the clean white of my freshly laundered underwear.

I can see through the windows of the motel – windows that won’t open for safety reasons, that have never opened for safety reasons – that the sky is orange, red, black, white hot and gold. That the sky is a disco no one wants to go to. Beyond the strip of motorway is the sickly abattoir and the disused circus tent, the chlorine-steeped leisure centre and the poorly maintained cenotaph – an impressive monument to the war dead, carved in polished obsidian. Less impressive is the hastily constructed extension to the noble column, poorly rendered in cheap materials and built to accommodate the new names that flood in daily.

By the second week of summer the illness that fatigued us became more pronounced in our children. The wet stuff that was inside them curdled and spoiled. Green where it should’ve been red, stone where there should’ve been jelly and finally powder where there should’ve been bone. All of it leaked out from the pores of their skin. Small, yellowish oblongs, smooth and cold to the touch. When they finally passed away I felt relieved. I had never wanted to think about a time when they would live without me. To paraphrase something I’d once heard: it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of me.

“To paraphrase something I’d once heard: it was easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of me.”

I unmute the TV and go to the bathroom to fit a contraceptive device. The sink and the bath are filled with ash and I feel a flicker of anxiety about hygiene, about putting something inside myself in this environment. My hair, skin and clothes smell of campfire. Likewise my contraceptive device. But the towels are surprisingly clean, fluffy, luxurious even, just normal towels without scorches or stains. I spread them on the floor of the bathroom so I can lie down. I close my eyes.

After the death of our children my husband became increasingly martial. He donned a uniform and boots, enjoyed marching more than he had previously. He longed to be involved in the rationing of supplies, the guarding of the reservoir, the dispersion of crowds. Yet, despite his newfound love of discipline, he was not interested in restraining me. Instead, he looked sadly at my heavy breasts that childbearing had destroyed whilst zipping up his khaki fatigues. It was at this time that my affair with Adam began; he seemed so much more interested in touching my body and looking at my face. If my husband wasn’t carrying out his self-imposed military duties, all he was concerned with was staring at pictures of our children. Pictures of them enjoying playgrounds and theme parks, pictures of them smiling at smokeless skies, pictures of them with mouths full of teeth and their intact fingernails curling around the laces of the light-up shoes they wore on their tiny, perfect feet.

“If my husband wasn’t carrying out his self-imposed military duties, all he was concerned with was staring at pictures of our children. Pictures of them enjoying playgrounds and theme parks, pictures of them smiling at smokeless skies, pictures of them with mouths full of teeth and their intact fingernails curling around the laces of the light-up shoes they wore on their tiny, perfect feet.”

A great number of hours have passed but Phantom Menace is still playing when I leave the bathroom, an endless scene in a senate so vast it stretches the limits of credulity. The light from the motorway casts a viridian depth in the room, making me feel like I’m in a film about people having an affair. On the bed there’s an inferior sparkling wine that Adam must’ve brought along. He opens it up and pours it into the mugs that sit next to the tea- and coffee-making facilities. We drink in silence for a few hours and then, feeling bold, I use my mouth to open his mouth. I reach all the way back with my tongue to lick at his soft palate. It tastes sharp, a sour ice-cream stench. I long for it in a vicious way.

‘Adam, tell me what you would like me to do.’

‘Well, what do you want to do?’

‘I want you to tell me what to do.’

‘Yes, but first you tell me what to do.’

‘I’m telling you I want you to tell me.’

‘And I’m telling you that I want you to tell me too.’

It feels impossible to voice my desire to him. When desire is secret it seems a torture, but when it’s revealed it’s an unbearable humiliation.

And so, this back and forth, this round and round, this will they or won’t they, this endless attrition continues for weeks. The sky lights up and is extinguished over and over; gunfire has destroyed the motorway. The motel taps have stopped working and we’re rationing the toilet water. We’ve become so dehydrated our piss has thickened to syrup but still I beg him to tell me what I should do to him. Now it is Phantom Menace hours all the time, given that it’s the only thing being broadcast. The machine at the television station must be stuck in a loop and there’s no one there left to fix it.

“Now it is Phantom Menace hours all the time, given that it’s the only thing being broadcast. The machine at the television station must be stuck in a loop and there’s no one there left to fix it.”

‘Adam, tell me what you would like me to do to you.’

‘Greta or Virginia, you tell me what you would like me to do to you.’

‘You tell me.’

‘You tell me.’

‘You tell me.’

My husband is most likely dead by now, my parents and brothers too. No doubt entire species have been wiped out by whatever it is that has happened to us. My house and all my lovely things are probably destroyed, as well as the company we work for. I am no longer a regional manager and can only assume that Adam is no longer a pathetic waste of space.

‘You tell me.’

‘You tell me.’

I shift my weight from one buttock to the other, disturbing the heat of my brutally damp gusset.

‘You tell me.’

‘You tell me.’

A sweet and familiar odour rises from between my legs when finally, Adam’s small voice cuts through the smoke-heavy air of the motel.

‘Let me brush your hair, let me shampoo it and stroke it gently. Let me hold your hand and whisper compliments into your ear. Let me pass you this cardigan as the temperature drops. I can show you how to properly fit a gas mask, how to sterilise your contraceptive device. I can introduce you to my friends and acquaintances, take you to the grave of my poor dead brother and one of my parents —my mother or my father. I can call you my girlfriend, my love.’

When he strokes my back and gives me the lightest of kisses right on the tip of my nose I am reminded of my husband and start to gag. I want to scream “no, not like this Adam, not like this!” but how can I let him know what I want?

I must sharpen my beak, dislodge the venom that lives at the back of my throat and spit it out at him. His liver is plumped, shiny red-brown in the faltering light from the ruined motorway, ready now to be pecked out over and over. I steady my hand and slap his face.

He holds his own hand to the slapped spot, his mouth a shocked little ‘o’ and his eyes watering thickened tears down the sides of his nose.

‘Now lie down,’ I tell him.

He does as he is told and I pin him to the motel bed, the mattress well past its best, the sheets worn soft and warm. Now I press my knees into his chest and dribble a line of spit straight from my mouth down into his. I watch him swallow.

‘Greta or Virginia, more,’ he tells me.

I work my mouth to produce more saliva; it takes a while, and even then, is just a few small drops that fall in or around his mouth.

‘More,’ he says again.

‘Don’t be a little bitch Adam,’ I say, curling my fingers around his neck, tightening them fast, thumbs pressing further into his windpipe. ‘This is just a sexy game and you’ll love it.’

And he does love it, for a while. The thick meat of his pale tongue flicking in delight, then slowing and lolling to the side before stopping altogether and lying stiff and unmoving at the side of his mouth.

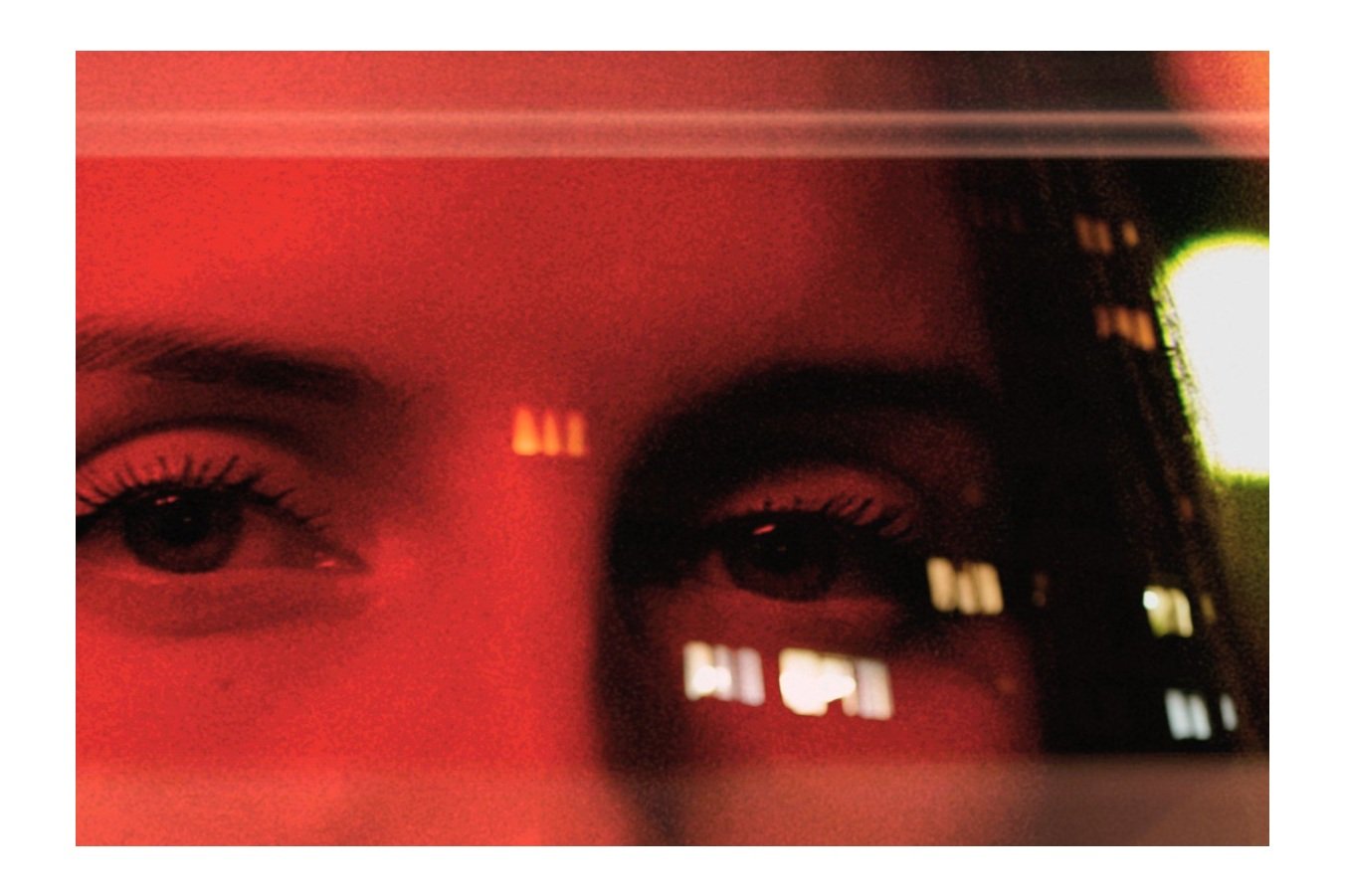

Now, unless you count cadavers – which I don’t – I am completely alone. The room’s new coldness brings about a devastating thirst and I peel a fur-lined tongue from the ridged roof of my mouth, part my lips in anticipation. All the toilet water is gone and even my spit has evaporated from Adam’s chin and cheeks. Outside, beyond the churned-up roads and scorched playgrounds, scant strangers are sifting through the ruins of the supermarket for the last tins of expired hotdogs, but still this endless film plays on, lighting my face red, blue and purple with its fluorescent swords. ▼

Image: Daniil Lobachev

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.