The Blue Fox – by Michael Burrows

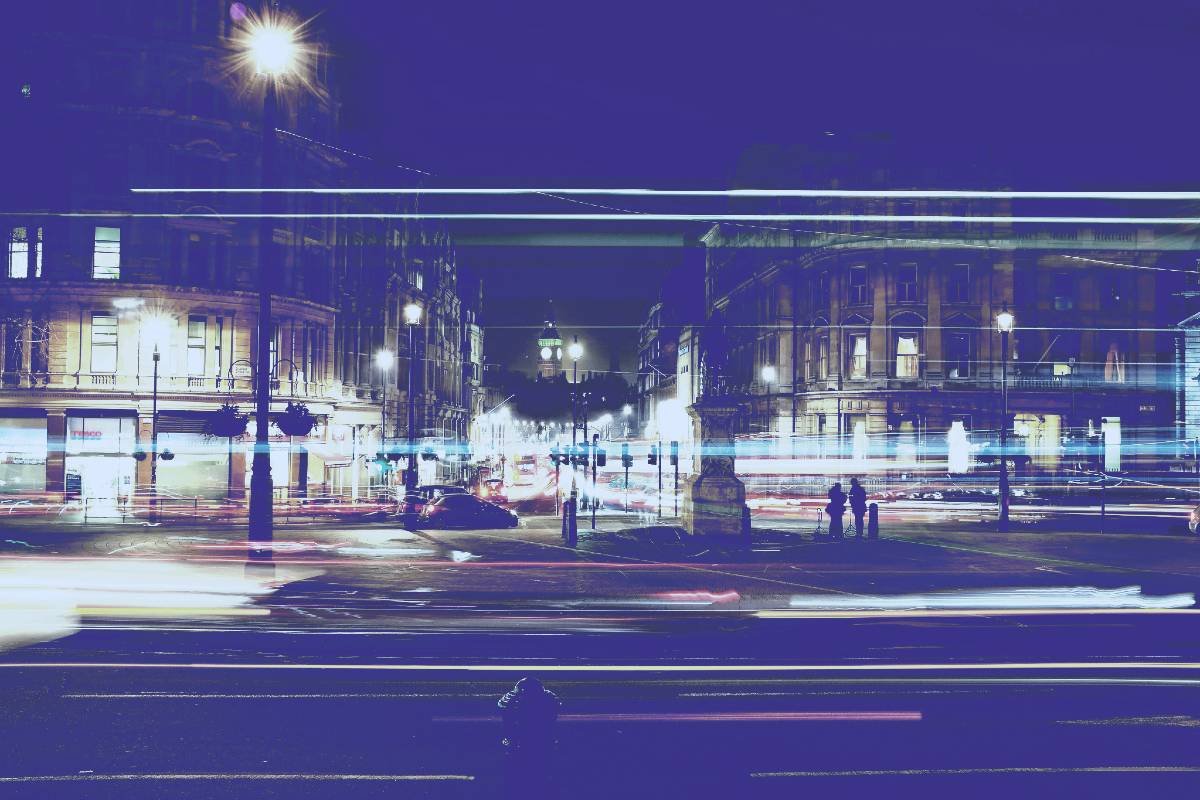

ISLAND | ONLINE ONLY“We create our own London; build our own streets and design our own St Pauls, but always, on the fringes, something lurks: crying in the night, knocking over dustbins, tearing out our hearts.” [1]

[1] Lamont, Chester, To Each Their Own: London in Literature, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1958, pp. 66-67. Lamont goes on to describe the streets of London as a proto-labyrinth, continuing the theme picked up by Grant and Estable in their genre-defining ‘Minotaur and the Myth’ (included in Strange Thames: 13 Essays on The New London, Fresh Inc. Publishing, London, 1957). For Lamont, the city of London becomes a challenge, something he must conquer in order to progress; a creation myth for his own writing process.

Wandering the back streets of Soho, encountering prostitutes and drug addicts playing hopscotch, sidestepping the canine and human excrement, noting the beauty in sex shop window displays

XXX DANCING GIRLS XXX

Down dark stairways wrinkled men watch his every step, empty cans tinkling by their feet, the pre-dawn soundtrack of windswept glass and someone somewhere shouting at someone somewhere.

Into this environment Lamont introduces his own Minotaur, the creature gnawing at him, chasing him through alleyways, catching up with him in the back rows of snuff films, tearing his bowels out in adult bookstores. By the end of the book, the reader is unsure whether they have just read a defining piece of literature or the ramblings of a madman.

Remember that time we argued from Leicester Square to Trafalgar Square at four in the morning? And there on the corner you turned and spat, “I fucked him. Are you happy now?” [a]

[a] This would be about two years ago, when I was still working in that cocktail place on Brewer Street; waking up hungover each morning to write, teaching English classes in the afternoon, and starting each evening shift exhausted. The regulars would come in and say I needed sleep but still shout me another, so by 3 am I’d be stumbling out of the late-night tequila spot next door and falling asleep on the N91 with my head resting on whoever was unlucky enough to sit next to me.

This was when we were still properly dating – sure, the cracks had started to spread, but the dam wall still held, the waters behind looking murkier with the winter rains, the metaphor beginning to falter the longer I stretched it. We’d finish another late shift and I’d catch your eyes as you wiped down the bar; next door the tequila would pour, our legs touching as we sat together, then back once more into the darkness of our empty bar to fuck in the toilets, laughing as the cleaners turned on the lights and we emerged with sheepish grins, buckling our belts, wiping our mouths, giggling into the dawn.

But some nights there’d be screaming on Regent Street, or back-alley fights about stupid things, my jealousy or your pride, and London would drop away into inky darkness. What Estable would call ‘Piccadilly’s gaping maw’ would open and swallow us whole, and, dumb rabbits that we were, we’d skip hand-in-hand into the darkness, scoffing the breadcrumbs that would have guided us home. [i]

[i] Jason Estable, ‘London Derriere: On the Dark Side of the Nation’s Capital’ from Strange Thames: 13 Essays on the New London, p. 164

And I broke down right there in front of the closed Pret, kneeling in the street like every clichéd romcom I’d ever watched, unbelieving, until, fuck you, you turned and said something like “thasnottrue, sorry, onlysaidthattohurtyou.”

And I believed you.

In Trafalgar Square at that time there was a giant Blue Fox, six metres high, on the Fourth Plinth – the artist’s name eludes me – a twisted metal scavenger looking down on us as I wiped snot on my coat sleeve. You wrapped your sorry arm through mine and we swaggered across the pavement under his gaze, and then, like babies, lowered ourselves step by step on our arses to the bottom.

Behind us and to our right came the sound of rending metal, a six-car pileup, the scream of twisting iron. When we stood up the Fourth Plinth was empty. You swore you saw a giant bushy blue tail disappearing down Pall Mall – but then, you would say anything to hurt me.

We caught the N91 back home, fell asleep entwined on the top-floor front seats and woke up a stop late – forced to run downstairs, streaming into the pre-dawn still buttoning-up and regloving. A five-minute walk back to your place, rubbish blowing down the street in little chip- packet whirlwinds, sunrise peeping over the houses, when we heard them.

Google calls them ‘chilling screams’ and ‘rhythmic whines’, but I’ve always found them more sensual, more orgasmic, grief stricken. You hear them, lying in bed at night, and wonder what otherworldly creature could create such noises. And then you realise it’s just foxes.

Always foxes.

Or does that reveal too much about my sex life?*

* It does.✪

✪ From Timeout, London Edition, 4th February 2022, p. 23:

“We were all frightfully shocked to find out that sculptor Antonaya Natalishkova had lied to us and the wider art world. Waking up that morning and finding the Blue Fox had disappeared was distressing enough, but to hear the artist’s tearful admission – that instead of sculpting the work from heavy iron girders, as we had been led to believe, she had merely spray-painted a giant mega-fox (one that she had found in the wild) with Royal Dusk™ blue paint and chained it to the plinth – robbed us of some of the magic of art. It all felt a little tacky. Following the Blue Fox incident, London’s art scene has suffered a remarkable fall from grace, while London’s rubbish bins continue to be scrummaged and ransacked in the early hours.”

We fell asleep as the sun rose, and I was late for my lunchtime lecture on ‘Scones with Cream & Enjambed Lines: Poetry of the Afternoon Tea’.

We had maybe six more good months.✚

✚ Some nights I wake screaming, my sheets soaked, from dreams in which I am chased down those streets by a creature I can never see.

Some nights I wake with wet sheets from different dreams.

Same streets.

As Chester Lamont says:

“We create our own London; build our own streets and design our own St Pauls, but always, on the fringes, something lurks: crying in the night, knocking over dustbins, tearing out our hearts.” [1]

▼

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.