The Intimacy of Daily Life: The News is the Weather - by Rosie Flanagan and Miriam McGarry

ISLAND | ISSUE 157Rosie Flanagan and Miriam McGarry travelled to Iceland to participate in the Printing Matter residency at Skaftfell in September 2018. They shared their reflections with Island ...

Tasmania and Iceland sit at almost opposite ends of the world; remote islands of disparate wilderness that are as distant as the 17 000 kilometres that separate them. The premise behind our application for the publishing residency there was simple: islands, as books, have delineated boundaries – and yet, the identities of both are formed through interactions and exchanges that extend beyond the lines of a map or the borders of a page. We wrote to Skaftfell, who run the Printing Matter program, and told them that we intended to publish an island.

This abstracted idea seemed meaningful from a distance, but once we arrived it proved to have little tangible meaning. From Melbourne and Berlin, we travelled with a backpack full of dried lentils (to combat Icelandic prices), and a predetermined idea of what we would find. We tried to lasso our neat concept of island around a place that, rightfully, denied our fixing. Our arrogance of ‘knowing’ slowly eroded, replaced by the gentle revelations of place – the particular and the universal, the news and the weather.

*

The town of Seyðisfjörður was established around one of the deepest ports in Iceland, nestled between mountains in the east fjords of the island. In winter, the serpentine road to the pass is frequently snowed over, and the town cut off. This sense of separation feels pronounced to us, marooned without a car, but it doesn’t seem to concern the residents. Many have moved here for such distance; a remote place on an already remote island.

Despite its isolation, the 700-strong population is increasing so rapidly that there is both a rental shortage and a waiting list for the local primary school. The growing cultural and tourism economy supports four arts residencies, three pubs, and a single supermarket that stocks woollen hats and socks, fridge magnets, tropical fruits and three types of overpriced cheese. The bottle shop is open for two hours a day (and not at all on weekends) and sells cask wine at 48€ a box. You would not call Seyðisfjörður gentrified, but traditional lopapeysa jumpers and Copenhagen street fashion sit side-by-side drinking beer at the bar.

Twice during our stay, the residency organisers drive us over the mountains to Egilsstaðir to buy groceries from a discount supermarket with sunshine-yellow shopping bags emblazoned with bright pink pigs. Driving home, Tinna, one of the residency organisers, describes the history of the landscape that rolls past our windows – a geographic introduction to place. As we pass the crest of the mountain, she tells us that a tunnel to link Seyðisfjörður with Egilsstaðir has been proposed. Hollowed through the mountains, this underground bridge would be both a convenience and a loss, a connection and a destruction.

Seyðisfjörður was the first place in Iceland to have a telephone. ‘Pieter the elder’ runs the Technical Museum that houses this piece of material history, alongside the ancient letterpress and lithography equipment used by the Printing Matter residency. Pieter grew up in America, but seems as native to the fjord as the Icelandic sheep. We quickly learn that he has assumed a kind of mayoral role in the town, overseeing everything from the museum curation to the small kiosk that sells tickets and hot drinks at the port where the ferry, the Smyril Line, docks. Everyone here has multiple jobs, including ‘Piotr the younger’ – an artist from Poland who splits his time between work in the museum and cleaning the local hospital. It is a small town, one whose identity has increasingly become attached to art production and its creative community.

The houses we occupy during the residency are all owned by artists – ours by a Brazilian man who splices his year by seasons and hemispheres. Friends in ‘downtown’ Seyðisfjörður live in one of Swiss artist Dieter Roth’s properties. His imprint is on everything in this town, even the limited housing stock that waves of Danish and Polish artists are trying to procure. One evening at Skaftfell we watch a documentary about him, with the sound of our residency instructor Åse knitting in the background.

He is an exceptional character, a true art-monster. A group of eight women sit in the fading dusk light and watch the myth of the tortured male genius unfold. His ex-lovers describe first his charismatic allure, and then his requests for them to destroy their clothes and their books, to erase all identity from their being – he wants to shape them anew. Everything was a project to Roth, women included. Åse remains quiet as we watch, but the aggressive click of her knitting needles does something to imply her feelings towards this type of man.

Roth’s estate, now run by his son Björn, owns Skaftfell, the arts centre where our residency is housed. In the pizza parlour that sits at the base of this building, there is a wall of his original prints. We scrutinise them often over margherita pizzas and the discounted beers bought with our laminated ‘artist in residence’ cards. At the Technical Museum, we print on his lithography stones, whose Brobdingnagian size requires two people to lift them. Warned against breaking them, we joke of creating an empire selling ‘Dieter’s Rocks’ to the tourists in the town. In a place where the cultural economy is based on the creative industries, our impression is that while the town is run by women, it is still defined by men.

The following morning, Åse asks if we would like to swim in the fjord with her. ‘At 8:15 there will be sun on the beach.’ Past the port and the shipping yard, full of rusted cars and boats that haven’t seen water in moons, lies a small cove of black sand. At ten past eight we arrive, swathed in thermals and scarves – it’s overcast. The sun breaks through at 8:15, just as Åse forecast. The two Danish men who run LungA School, a fine arts masters program housed in an old fishing shed in the town, are building a sauna at the edge of the beach. We watch as Åse greets them: her, in bare feet, wearing a grey bra with a towel around her waist. Them, in workers’ gear and Blundstones that match our own. Is there anywhere that Blundstones have not reached?

People from Seyðisfjörður swim all year round. The water from the fjord remains the same temperature regardless of the season. This body of blue fluxes constantly, drawing water from both the mountains and the sea. As a result, it never freezes, despite the cold. Whales are common here. A woman from the town found herself amongst a pod of orcas on her morning swim just weeks before. But there are no whales on this day. Just glacial water washing over us, our bodies slapped pink from the cold.

“But there are no whales on this day. Just glacial water washing over us, our bodies slapped pink from the cold.”

On Tuesdays the Smyril Line slides into the harbour, spelling NORRONA in high-beam and taking possession of the dark. Northern Lights of another kind spill through the thin lace curtains that veil every window in town, and illuminate a shoreline that in the late 2000s was reshaped to accommodate the scale of the ferry. Reclaimed (newly claimed) landfill crept into the fjord to facilitate the growth of the tourism market. A crudely material articulation of economic geography – ‘form follows finance’. The ferry itself remains Danish sovereign territory, exchanging Danish krone on board: docked at an invented body of land. Two nights a week, part of Denmark shines through our windows, burning acrid chemicals in the Icelandic fjord, and paying taxes to support the Danish economy. And now, in Melbourne and Berlin, small rocks from the reclaimed foreshore sit on our bedside tables and window sills. Tiny islands.

“And now, in Melbourne and Berlin, small rocks from the reclaimed foreshore sit on our bedside tables and window sills. Tiny islands.”

Every morning after breakfast, we go through the routine of trying to establish which of the four colour-coded bin options is appropriate for our baked bean tin. We wash out the aluminium and discuss Claire Louise Bennet’s story Stir Fry: ‘I just threw my dinner in the bin. I knew as I was making it I was going to do that, so I put in it all the things I never want to see again.’ This abandonment isn’t possible in small places. The chains of responsibility refuse unpicking or ignorance; you are enmeshed and exposed in complicity. In Seyðisfjörður, nothing separates the drain and the fjord – the spatiality of consumption. At the studio, we avoid turpen- tine and methylated spirits, instead cleaning with organic coconut oil that casts an incongruous tropical perfume. True costs are illuminated in an uncluttered environment, where there is direct line-of-sight from the licorice wrapper to the landfill. We make painting ink from blueberries and rhubarb. With our grubby purple fingers we place the leftover pulp in the green-lidded bin. We dutifully collect scraps at night, never knowing which bucket or bag they belong to. We’re careful disposing of our few precious bottles of wine, as once binned they are sorted by hand.

“We make painting ink from blueberries and rhubarb. With our grubby purple fingers we place the leftover pulp in the green-lidded bin. We dutifully collect scraps at night, never knowing which bucket or bag they belong to. We’re careful disposing of our few precious bottles of wine, as once binned they are sorted by hand.”

When we arrived in early September, the hills were thick with blueberries; the mountains coloured in umber and green, their dark angular peaks slicing the blue of the sky into ribbons of light. On our early walks we ate the fruit till our mouths were stained, and watched the deep navy of the fjord dance with white, flecked with an impossible amount of sunshine. When we departed, we were also farewelled by brightness. The woman at the Avis counter informed us that an extreme weather warning had been issued for all of Iceland, as she gestured down the road to the mechanic who would put our winter tyres on, three months early. Later that afternoon, we drove through the mountains, the entire landscape obliterated by the white of a snowstorm. Such elemental drama is common in Iceland, in a way that was once uncommon in Tasmania. Now the precariousness of the environment – even when not subject to the push and pull of tectonic plates – seems frighteningly apparent. We have learned to submit to the unpredictability of places, and in turn, to protect them more fiercely.

“Now the precariousness of the environment – even when not subject to the push and pull of tectonic plates – seems frighteningly apparent. We have learned to submit to the unpredictability of places, and in turn, to protect them more fiercely.”

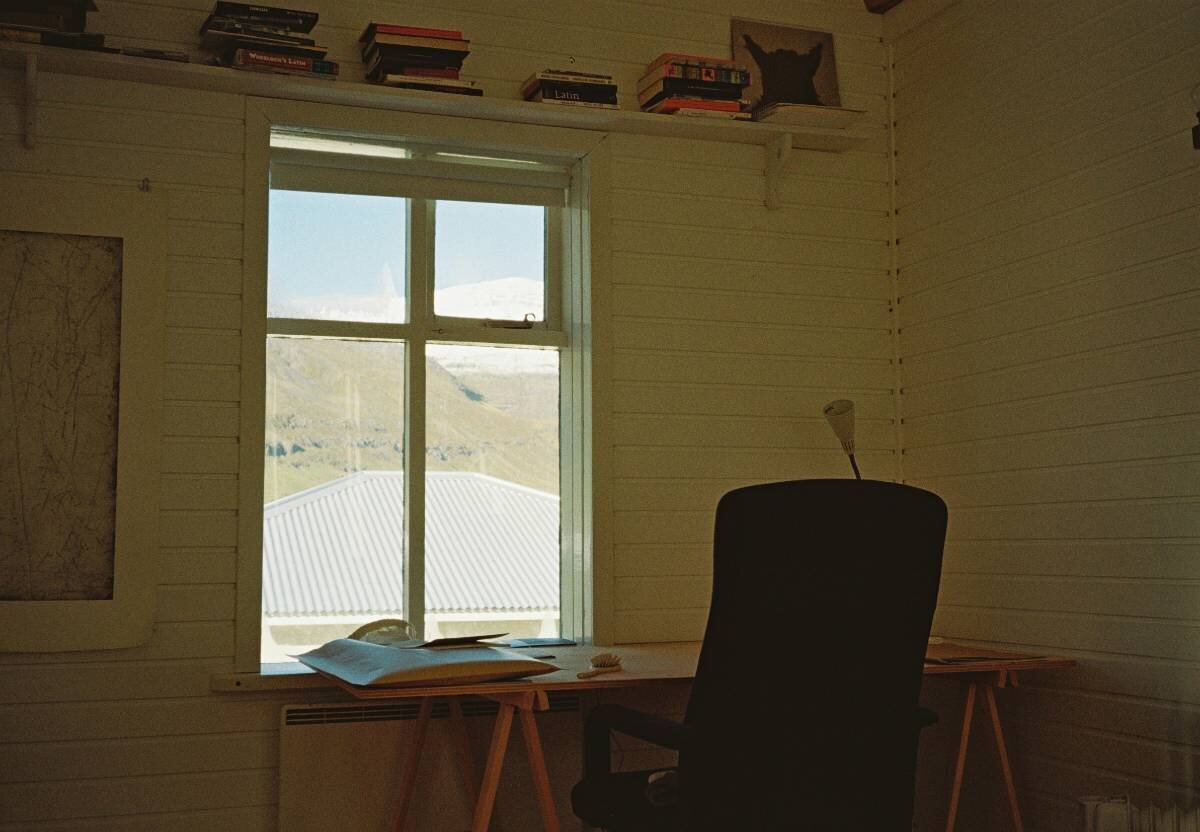

Our time in Seyðisfjörður was charted by water and weather; we mapped tides, and researched the rate at which Iceland was expanding from a fissure of movement at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge below Þingvellir. We worried about the impact of tourism, baked damper and spoke of the particularities of a place so different from our own. Mostly, we looked out the windows and watched the changing faces of the mountains. We published a book of firm borders and fluid edges, an edition of just one. How could anyone be so foolish as to imagine they could publish an island? ▼

All photographs by the authors

This arts feature appeared in Island 157 in 2019. Order a print issue here.

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.