The mystery of the lost hours – by Sue Brennan

ISLAND | ONLINE ONLYHow far is it between me and the barn? How many steps? Will my spittle reach that rock? If I walk towards it with my eyes closed, will I stumble? How far will my voice travel? Will it reach Dad in his office? Will he look up from his writing and say, ‘What’s that stupid girl up to now?’ and go back to work?

‘Joey,’ he calls out the window after some time. ‘Get in here now.’

If I cry one of those open-mouth sobs, will I even hear myself?

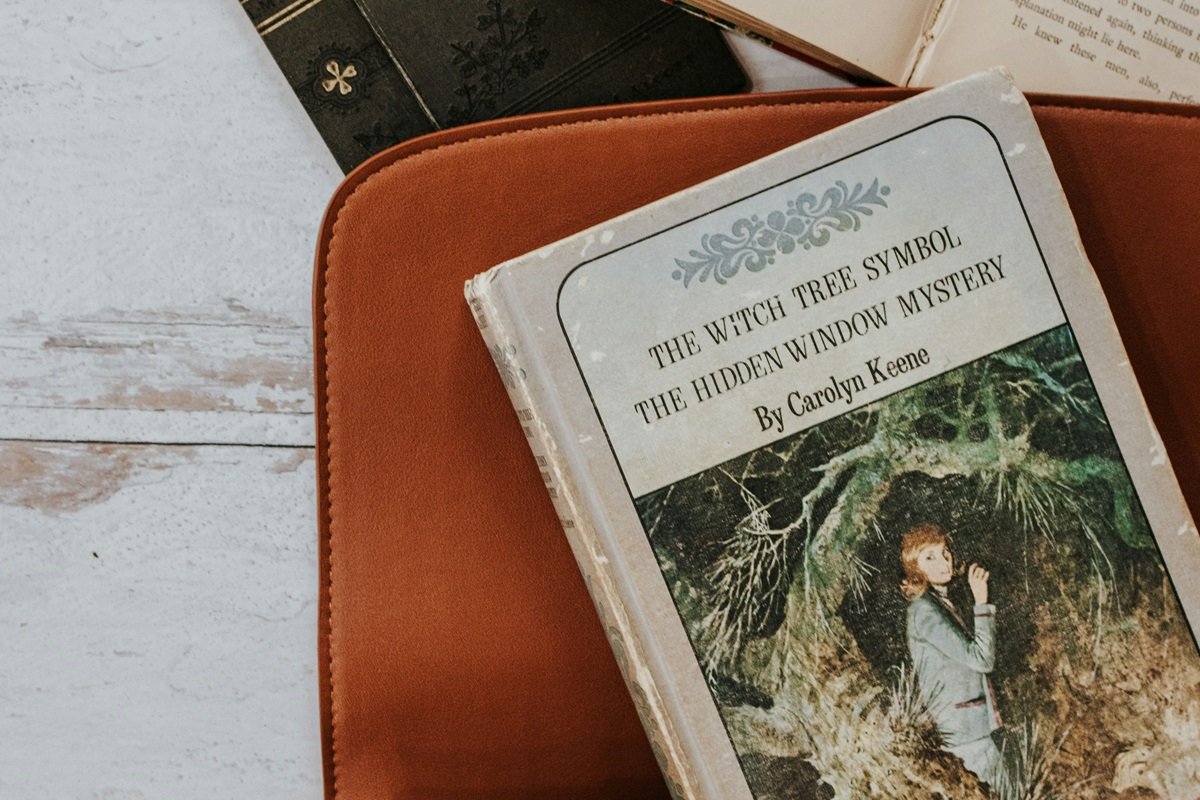

I’m lying on my back in the grass looking up at the insipid sky. The Secret of the Golden Pavilion—A Nancy Drew Mystery is sitting up like a tent on my stomach. It’s the only book in this house that I can handle. Not even one bird has passed over me. I won’t go in until one does.

‘How’s the writing going, Dad?’ I ask by way of showing love.

We are eating the dinner that I prepared.

‘Good,’ he says, and tells me about the strange detours down which his research has taken him. He can’t help but follow one arresting character who’s turned up, demanding attention.

‘Who is he?’ I ask.

‘A Scottish fellow. Swarthy as a pirate. Charming as well, but I can’t trust him. He’s got a secret.’

‘I wonder what it is,’ I say, wishing I had a road ahead of me with detours to take. But my journey has ended here, on the eve of my eighteenth year, in this house, with this parent. I hadn’t realised it would be so truncated.

‘I’ll give the character a day or two,’ Dad says. ‘I can’t spare him much more than that.’

Dad has a deadline. The novel must be completed by the end of the year, and then, I guess, we’ll move back to the city. The owners of this property are somehow connected to his publisher. They’ve been kind enough to offer us this place to stay so Dad can finish his novel, and I can get over what happened.

‘I hope the character takes you somewhere interesting. I’ve made some dessert, by the way.’

‘Hmm,’ he says. ‘Yes.’

My room in the house overlooks a small disused foundry. I can see broken white casts, like bones, in the dirt. In my Year 7 art class, we were shown how to make blocks of plaster of Paris. Then we carved them into shapes. One girl carved a perfect sphere, and we all attempted to copy her. The teacher gave her an A and the rest of us a B.

‘The property was once an artist colony,’ Dad said when we arrived. ‘Be careful in the barn. There’s scrap metal and hooks and nails. From a sculptress.’

I ponder that word, sculptress. I think about that woman in the barn, powerful enough to bend metal to her will. Perhaps she slept in the bed I sleep in. I pull a crocheted blanket around me like a cloak. The mornings are cold here in the country.

There’s a bicycle I can use. It takes me an hour to ride to the nearest town. Dad and I drive in on Saturday mornings and fill the car with supplies. On Wednesdays, I cycle for the exercise, to pick up something we’ve forgotten, and to get used to being unchaperoned.

I feel childish in my pink cotton dress on the bicycle. I wear a baseball cap that was in the cupboard and pull my ponytail through the back. No-one my age rides bicycles anymore. Not unless they are dressed in lycra and riding in packs, or on slim-framed elegant machines in the early morning. Coming into town, there’s a hill that’s too much for me. I have to get off and push the bike up to the crest. I can see the tower of the post office, the modest spire of a church, and the cluster of houses and shops along the main street. I careen down, the lip of the baseball cap lifting in the wind, and pull into the carpark behind the supermarket.

I want to make a chocolate cake for my birthday. In the aisle with flour and packet mixes are little plastic bags of nuts, silver balls and coloured sprinkles. I can imagine Dad’s expression – he’ll be pained that he didn’t remember. Didn’t do anything. I’ll make two cakes, I decide. One plain and un-iced, the other as I want it to be. I buy a pack of candles.

‘Join the library,’ Dad told me this morning. ‘You should be doing something while we’re here other than staring up at the sky.’

It’s as close as he’s come to telling me I’m a burden.

The library is down a side street in what was once a house. There is no-one in there other than the librarian, a woman in her fifties.

‘Hello love,’ she says when I come in. ‘You’re just in time.’

She hands me the end of a roll of paper.

‘I’ve got to get this pinned up,’ she says, ‘and I can’t for the life of me do it by myself. It keeps rolling up. Hold it while I pin it, will you?’

Together we manage to pin the blue paper to the wall. She tells me this is for a display she’s making for the local school children for book week.

‘Been here before?’

‘No.’

She says, ‘Well, look around. Let me know if you need some help’.

I look at the stand devoted to award-winning writers. There are several there that I’ve heard Dad criticise for being crowd-pleasers. I look for one of his books but there are none, not even the really famous one from twenty years ago. I find a row of Nancy Drew books that are worn, the pages fly-specked. I take three to the desk where the woman is tracing around a plate on a piece of yellow cardboard.

‘Nancy, hey? Odd choice. Got your card? Or the app?’

I tell her this is my first time here, and she asks me a series of questions to sign me up. It becomes clear that I cannot join. I don’t live here.

‘Not a utility bill in your name?’

‘Dad handles that stuff.’

‘Unemployment card?’

‘I’m not on the dole,’ I say. ‘Sorry. I’ll put these back.’

She calls out to me when I leave.

‘Happy birthday for Sunday, Josephine.’

‘Your mother has emailed me,’ Dad says.

We are both unsure what to do about it. It’s been almost four years since she left.

‘It’s like she went off on a holiday,’ he says. ‘Look here, this part: “I’ll be back in Australia by the end of the year. It would be lovely to catch up with you both. A lot to tell. A lot to explain.” Catch up? What kind of narcissist says that?’

‘Do you think she’s married?’

‘She’s a bigamist if she is. We never divorced.’

I imagine her and the sculptress as one woman. Carefree. Eccentric. Self-obsessed.

‘Joey,’ she said before she left. ‘Don’t hate me forever, okay? Just for a while.’

I never hated her. I was thirteen when she left and found some crazy friends to distract me. They were so amused by my bravado, so envious of what they thought was my freedom. It wasn’t freedom. It was neglect. Dad embarked on an affair with a family friend almost as soon as Mum left. Funny how he thinks I never knew. While he was on book tours with her, I had the run of the house. What thirteen-year-old wouldn’t take the money left for school excursions and food and spend it on cases of beer and takeaway pizza to enjoy with her crazy friends?

Maybe I should start hating her now.

There are metal hooks and nails, yes, but they’re not the most dangerous things in the barn. A circular saw mounted on a heavy wooden table is like something from a horror movie. It could dismember a body. Then there are cylinders of gas, a crate filled with shards of coloured glass, a blow-torch and drill. Every object is imbued with malevolence. Despite this, perhaps due to the high ceiling and dust-filled air, it’s a good place to think. Perhaps it is because there are so many ways to harm myself in here—so tangible, so available—that I feel a measure of safety that I haven’t in some time. Certainly not out in the grass under the endless sky.

This is the perfect place to have my birthday cake.

The librarian’s name is Eileen, and when I tell her who I am – who Dad is, and what we’re doing here – she’s very interested. She finds three of his books in a section of the library that I didn’t check and tells me she’s read them all, but not recently.

‘I wonder if he would be interested in doing a reading, or a workshop,’ she says, and I tell her he probably would, normally. Right now he has this deadline.

She says she understands, but I suspect she’s going to ask me to ask him.

I take a few Nancy Drew books and sit in one of two comfy chairs by the front door. There is a table between them with a stack of magazines. It feels like a doctor’s waiting room. I can see the top of Eileen’s head as she sits behind the desk. I can hear her talking but don’t listen. I flick through the books reading descriptions of Nancy’s hair and outfits, her few interactions with her father, but mostly I just study the covers. The illustrations are always of Nancy, and sometimes her pals Bess and George are depicted too. But who cares about them? Nancy is the pretty one, the one with the freedom to do what she likes, the one with the dead mother. I wonder what happened to Nancy. She just went on and on. The eternal teenager.

After an hour, I put the books back and leave while Eileen is up a ladder at the far end of the library. Her shirt lifts as she reaches up to pin a picture to the wall. I can see the elastic top of her jeans and a band of freckled skin.

‘It’s not up to me,’ Dad says. ‘You can make your own decision about your mother. I’ve decided not to respond. Not now, anyway. I’m too busy with the book.’

‘I know,’ I say. ‘Forward me the email. I’ll think about it.’

He seems startled.

‘Really? After all…?’ He peters out and resumes eating.

‘The woman at the library wants to know if you’ll do a reading or something,’ I say, because it’s good for his morale to know that people are still interested in his work.

‘I don’t have time for all that,’ he says and chews thoughtfully. ‘Still, might be a nice diversion. What did she have in mind, did she say?’

‘A reading. A workshop.’

‘A workshop…That could be interesting. Of course, you know…’

He goes on to tell me about the writers that are from this area and how the burgeoning memoir genre has brought a lot of previously unheard voices out of the woodwork. It might interest me to know…

What would the mum-sculptress do? She’d say, ‘It might interest you to know, Daniel, that I have no interest in your opinions.’ She’d flick her hennaed hair and flounce out of the room with her kaftan or kimono trailing behind her. ‘I have to go to my studio now,’ she’d say. ‘I need to create.’

‘Tell this Eileen to give me a call,’ Dad says. ‘The sooner the better.’

I read the email about twenty times. It’s only seven lines long, and it’s the only email in my inbox. I don’t email anyone and they don’t email me. Me and everyone have come to this arrangement.

‘Tell Joey that I hope she’s well,’ Mum writes. ‘No, not well. Strong. I hope she’s strong and fierce. I know that my leaving was the best I could do for us all.’

I am neither strong nor fierce. I’m as fragile as a dandelion. If you so much as breathe on me…

‘This has come together quickly,’ Eileen says and looks pleased.

Today, she is wearing make-up, and large hunks of silver stretch the hole in her ear lobes into thin lines. The main room of the library has been cleared and tables arranged in a circle. There are eight women and two men seated with cups of coffee and tea. Some have iPads in front of them, and some paper and pen.

‘Joey,’ Dad says. ‘Go and print this off, will you? I thought of it last night. It’ll be a great addition to the program.’

I am here to help. I made lamingtons from scratch for morning tea, and I’ll go fetch lunch from Nadia’s Cafe when it’s ready. I go to the printer with the staff card Eileen has given me.

I hear people asking Dad questions, and then his long answers. His voice sounds different from the voice he uses at home. I find it hard to concentrate. I sit in the chair at the entrance and begin to nod off. I’m tired because I was awake for most of the night. It happens sometimes – I feel wired and brittle, as though lemon juice was coursing through my veins.

I went to the barn using a torch to guide me across the desolate yard. There was a strong wind, not quite a gale, tearing at my hair and jacket. The barn has electricity, but I didn’t turn the light on. The moon illuminated it with a sickly light. There was a battered sofa in one corner, and I sat there with my knees up, running the beam of the torch over a stack of paintings hidden in the shadows. Some of the paintings were stuck together but were easy to tear apart. They were dull pictures of landscapes, and I felt an urge to deface them. Like a tug from my past-self that said, ‘You would’ve done that once. Rip them to fucking shreds.’

What would Nancy do in The Mystery of the Old Barn? How would she solve The Mystery of the Sultry Sculptress?

‘Joey,’ Eileen says. ‘Josephine, wake up. Run along to the cafe, will you?’

My father is looking at me disapprovingly, but the other writers are indulgent. Their expressions say, ‘Isn’t she sweet?’

They think there’s something wrong with me. They think I’m special.

My father and I are fighting. Really going at it. It’s what happens when we try and keep the shit all pushed away out of sight. Periodically, we just erupt. The trigger, to his mind (and he won’t let go of this point) was him sleeping with Eileen.

‘I’m well and truly separated,’ he yells at me. ‘She’s not married. It’s age-appropriate. God I hate that phrase, the very notion of it. You tell me what’s wrong?’

I couldn’t care less about him sleeping with Eileen. I found it amusing to discover her barefoot in the kitchen making him breakfast, and I’d been suitably cordial. What I didn’t like was that he’d told her what happened – his version of what happened. I knew before she even opened her mouth. She looked at me with contempt and had the hide to say, ‘Well madam, what time do you call this?’

As though I’d just woken up. As though I hadn’t spent the night awake listening to them rolling about like a couple of old buffaloes. As though I hadn’t heard them up and down the stairs, opening and closing doors as they brought wine and God knows what else up to the bedroom for their midnight feast. As though I had anywhere to be other than here.

‘I don’t care, I don’t care, I don’t care,’ I yell back at Dad. ‘Sleep with who you like but keep me out of it. How dare you tell her—’

‘—Keep you out of it? You’re nothing to do with—’

‘—I know you told her about me—’

‘—Move on, Joey, move on—’

‘—I’m trying to—’

‘—Your mother and I—’

‘—It’s not about her, you idiot—’

‘—Stop lying! You’ve been emailing her, haven’t—’

‘—I’m not lying. What you told Eileen is a lie. You—’

‘—Eileen and I are adults—’

And so it goes on until we are both hoarse and trembling and breaking things.

His version of what happened: his wife left him, and his thirteen-year-old daughter went off the rails. She started running about with a bad bunch of older kids who got her into trouble, though God knows he’d tried to intervene. She missed doing her HSC because she was off her head on drugs, partying and sleeping around. Tried to frame herself as some kind of victim. Since then, she’s been docile as a lamb. He’s tried everything to help her, but she’s not a kid anymore. It’s time to grow up and accept that she had a shitty few years after her mum left. It’s time to stop sponging and get a goddamn job.

My version casts him slightly less as the deserted husband and heroic father but ends similarly. It’s time to move on.

Zach and Logan were two years older than me, from rich families, and the people they hung out with were way older, some of them in their twenties. Zach snuck out of his bedroom window to come over when Dad was away. His parents were super-religious and he was rebelling. We called ourselves JoLoZa – get it? – and referred to ourselves in the third person.

‘Is JoLoZa getting wasted this weekend?’ one of us would ask.

‘I’m pretty sure they are,’ the other two would answer.

The older crowd found us amusing. Being the girl, whenever I did whatever Zach and Logan did, it seemed even more outrageous. They shaved their heads, so I did too and looked like a cancer patient. When they tried MDMA, so did I. I’d have jumped off a bridge if they had. If anyone had suggested it. I pissed in a cup, once, or tried to, in front of everyone.

There was this guy, Bryce, who always taunted me that I was in over my head. He was ugly, and I felt sorry for him. The others gave him shit for being a dumbass middle-class loser. He didn’t have a cool car. He didn’t have looks. All he had was drugs. He was twenty-four, with sour breath and greasy jeans.

I found him in my bedroom once. Everyone was downstairs. Some people were dancing, some looking through the bookcases that lined the walls and saying, ‘Check this shit out.’ Logan and Zach were busy trying to hook up with some girls. I left the room, unnoticed and petulant. What could I do that would pull the attention back to myself? I thought of changing my clothing, putting on some stupid ensemble. School uniform and ugg boots. Pyjamas and high-heels.

‘Hey, pip-squeak,’ Bryce said. ‘You’ve got a lot of stuff, haven’t you? You’re one lucky little bitch, aren’t you?’

It felt so good to be seen.

‘Josephine,’ Eileen calls from the top of the stairs. ‘Turn that TV down, will you?’

I am watching a midday show about a nurse in the Second World War. I guess it was the battle scene where the volume suddenly increased that provoked this demand. I turn the TV down minimally. Eileen comes over to the house regularly now to act as assistant to Dad. She gets out of the car, all officious, and walks straight in and puts the kettle on. Eileen is overstepping her role, in my opinion. It’s one thing to be boning Dad. It’s another to behave as though she were my mother.

One night, I stayed out in the barn till morning. I slept on the musty old sofa imagining my head in the lap of the sculptress, her slender fingers combing my hair. A mob of cockatoos woke me long before I heard Eileen's car coming up the long driveway. I found them sitting on the porch with coffee and pastries from Nadia’s Cafe.

‘Up to your old tricks,’ Eileen said with eyebrows raised. Dad said nothing, looked out into the distance.

‘I was sleeping in the barn,’ I told her. ‘With the redbacks and the huntsmen and—’

‘I told you not to go there,’ Dad said. ‘You’ve got a perfectly good bed here in the house. I don’t understand you, Joey. I’m at my wits’ end.’

That was Dad being a parent.

Good, isn’t he?

I write to my mother. I write: Remember me, your daughter? Who do you think I am now? What have you been doing?

That’s all. Just those three questions. I want to freak her out.

It’s unusual – me and Dad alone, no Eileen. Apparently she’s down in Melbourne for a week visiting her kids. I make a lasagne for us and a green salad. There’s butterscotch pudding and vanilla ice-cream for dessert. I ask him about the novel, and he says Eileen’s help has been invaluable. She has an unforgiving eye when it comes to florid language. He asks me nothing about myself because what is there to ask?

I could tell him about the response I got from Mum and what I think about it, but I think it would rupture the tenuous hold we have on our relationship. And by the time we finish dessert, he’s had three glasses of wine and is almost friendly.

‘Why don’t we watch TV,’ he says. ‘What’s on?’

‘Pfft, not much,’ I say. ‘Those singing shows. Talent shows. Some cops and forensics stuff.’

‘Oh, that sounds dreadful. Well, when we get back home, we’ll appreciate the Apple TV a lot more, won’t we? Guess I’ll go upstairs and do some reading. Thanks for dinner, Joey.’

He doesn’t even kiss me on the side of the head.

I guess you don’t kiss the help.

‘Joey, my little Joey,’ she writes. ‘Remember you? Didn’t I hold you inside me for nine months? You’re my skin, my breath, my life, my soul. There isn’t a moment I haven’t thought of you. I understand you want to hurt me. You believe that you have been hurt. You’ve got to realise that people won’t always do what you want or expect them to do. But trust me – I did the right thing. I was suffocating in that marriage. I couldn’t mother you the way I wanted to. I couldn’t be the woman I wanted to be. HE wouldn’t let me. You ask me who do I think you are now, and I tell you this: I know you were a talented and intelligent child, so you must now be a talented and intelligent young woman. I have this image of you making your way in the world, perhaps going to university, perhaps not. But coming into your power. That sounds new-agey, doesn’t it? But I believe it.’

My power? Jesus. She hasn’t got a fucking clue. And, she didn’t answer my third question.

I hate her now.

Like fuel in my tank, it’s enough to get me out of here.

***

The Mystery of the Lost Hours

Nancy woke to find herself naked and alone. There were chunks of vomit in her normally lustrous auburn hair. She was thankful she didn’t choke and die. The house was quiet. Her chums, Bess and George, and everyone else had left. They’d been having such a swell soiree playing charades, drinking lemonade and listening to records. Why did they all leave? And where were her clothes?

Desperate, she trawled her memory for clues. She’d been wearing a cute plaid frock. Everyone had complimented her on it. She was busy being a good hostess – keeping the punch bowl fresh and turning over the LPs. She noticed a thin and surly man, a friend of someone’s, lurking in the hallway. She didn’t want to be churlish, so she’d smiled and waved. A good hostess makes everyone welcome.

She began to feel forlorn. Everyone was so involved in each other they forgot to pay any attention to Nancy. Her father was so often out of town these days, and despite appearances, Nancy missed her mother terribly. When she saw the strange man heading upstairs, her brow crinkled with concern. Perhaps he was looking for the restroom?

The man was in her room, on her bed. Nancy lifted her chin defiantly and told him to leave. It appeared, however, that the man was distressed and in order to give him some comfort, Nancy sat on the floor and tried to talk with him. Gradually the man began to relax and open up, and they shared their mutual loneliness. He offered her a tincture he said would make her feel better.

That was it! She’d been drugged!

Aghast, Nancy rose unsteadily from the bed and reached for her floral brunch coat. With horror, she saw the deep red stain of blood on the bed, and the pinkish smear on her slim, white thighs. With anguish, Nancy realised she was no longer a virgin. Ned Nickerson would never want to marry her now. No-one would!

When her father returned from his business trip, he was angrier than she’d ever known him to be. It was all Nancy’s fault. She should never have allowed unknown people into the house. And what had she been thinking, drinking something offered by a stranger? But there was more bad news to come.

Pregnant with the mysterious man’s child and fearing abandonment by her father, Nancy sought the help of Bess and George. Together, they found the services of an abortionist. Nancy convalesced at the home of Bess’s older sister, a compassionate and worldly spinster. When she returned meekly, her father embraced her and promised his eternal protection. What father wouldn’t offer sanctuary to his unmarriageable daughter?

When her father’s work took him to the countryside to stay in an old manor, Nancy leapt at the opportunity to leave the city and her awful secret behind. The manor had once been a thriving artists’ colony. The fresh air and wide-open spaces were a balm. Her father worked hard and Nancy kept house, helping in whatever way she could. They both grew strong, as did their relationship. Weekly, Nancy would ride into the nearest town, a quaint little settlement of no more than two hundred country folk. She became friendly with the charming librarian, Eileen, a stout woman of fifty-eight, full of witticisms and advice. Nancy began to concoct a plan that she knew would help them all.

Nancy contrived for Eileen to come to the manor, telling her about a collection of potentially valuable books in the barn. Eileen sat on the verandah with a glass of iced tea, waiting for Nancy to return with the books. Meanwhile, Nancy told her father there was a woman downstairs interested in the history of the manor. Busy but always affable, he trudged downstairs while Nancy watched through the living room window. Eileen’s ruddy cheeks glowed with robust health. They both laughed merrily when they realised they’d been set up. It was just a beginning but, oh, such a beginning!

As time passed and her father’s relationship with Eileen deepened, Nancy began to feel lonely once more. Eileen could never be her mother, no-one could, but her father deserved to be happy. Nancy didn’t want to be a burden any longer. It was time to make her way in the world, husband or not. She would go back to school and get a job, perhaps as a secretary, or a nanny, or a teaching assistant. Yes, the more she thought about it, the more she realised that’s what she wanted – a career!

The morning air was crisp. Nancy wrapped a plaid scarf around her neck and pulled on some woollen mittens. Her backpack contained only the essentials. The bike ride to the station would take almost an hour, so she couldn’t carry much. She had a thermos of tea and some blueberry scones for sustenance. She pushed the bicycle down the driveway, mindful of its squeaky wheel. Her father would be slumbering peacefully upstairs for at least another two hours. She owed him that.

When she got to the bottom of the drive, she turned to look back. The barn sat ominously beside the gracious manor. She’d found solace amongst the wreckage of the abandoned creations in the barn and the great pale sky above. Those lost hours in her bedroom could never be found, never be restored to her, their rightful owner. She was no longer Nancy Drew: Girl Detective. Now, she was just an ordinary girl on a country road, an orphan of sorts, heading to the city. ▼

Image: Mel Poole - Unsplash

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.