The world feels chaotic right now (though maybe it’s always been like this): a simmering anger and distress bubbling up into everyday interactions and leaving many of us frazzled, despairing, furious or lost. The writers and artists in this issue of Island are feeling that unsettling fizz and looking for ways to understand and express it. In the search, some of them are also finding joy. From the Yes campaign to emerging Palawa designers, from scathing fiction about Tasmanians left behind to a long and thoughtful essay on our relationship with nature, each of these pieces grapples with how we could make something better out of the world we find ourselves in.

Our graphic narrative project wound up in Island 169 with Joshua Santospirito’s ‘The last ever comic to be published in a literary magazine…ever!!’, but – provoked by his provocation – we asked Tasmanian artist Rosie Murrell to produce a post-last comic for this issue. Comics have become a vital part of Australia’s literary scene and we are keen for ‘What we become’ to mark the start of a new era for Island.

This issue also sees a continuing focus on the wonderful writers the University of Tasmania is supporting through its fellowship programs: 2023’s Hedberg Writer-in-Residence, Michelle Cahill, considers the role of lascar seamen in Australia’s colonial history with ‘A spectral presence’.

A flurry of funding announcements as 2023 turned to 2024 has left Island in a much more secure place: thank you to Arts Tasmania, the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund and Creative Australia for ongoing support. This funding gives us a foundation to deliver our planned activities, but we still need to pursue additional revenue to do everything we want to do in coming years. Most importantly, this funding allows us to continue the program of print and online publishing built up over the past few years by Island's previous Managing Editor, Vern Field, and Business Manager, Adelaide Reisz, who, along with the Board, created a solid foundation for Island during some tough times. On top of our regular program, we are looking forward to announcing several new publication opportunities and new projects – both on the page and in the outside world – that this funding enables. If you don’t already subscribe to our email newsletter, now’s the time!

— Jane Rawson, Managing Editor

Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize Judges’ report

This year’s judging committee for the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize comprised Eileen Chong, Esther Ottaway and myself, Kate Middleton. Over the course of several weeks, we each read the full range of poems entered into the prize and shared personal longlists that we combined to create an overall longlist for consideration. In our discussions arriving at a shared shortlist and eventual winner and runners-up, we talked about the qualities we looked for in a prize-winning poem. Among the ways we looked at these poems, we were particularly interested in those that not only combined excellence in form and technique, but were also sonically rich, addressed the emotions and contained surprises that rewarded re-reading. Indeed, one of the points of discussion we returned to was the fact that many of these poems ‘grew’ with each re-reading. By engaging in multiple sustained discussions, we could see where a poem might be deceptive in its apparent simplicity, but contain deep craft.

The winning poem, ‘The Burial Feathers’ by Yasmin Smith, addresses loss, ritual and belonging as it situates itself in the memory of one landscape – the Montana of sagebrush and the Flathead River – and the reality of a new landscape, the Australia of cockatoo feathers and casuarinas. In both landscapes, death looms: the speaker notes her great-grandfather ‘beneath the ground’ in Rosebud County, Montana, while in Australia the speaker walks ‘into the swell of the funeral parlour’, ‘regifting, returning’ the feathers of red-tailed cockatoos to her mother. The poem gathers intensity as the language becomes more dense in the final lines in which Smith writes ‘I ornate her with a warbonnet in death’, describing the feathers in a burst of equally ornate, dazzling richness. The poem remakes ritual: the traditional Native American war bonnet worn by respected men on ceremonial occasions becomes the improvised crowning with collected cockatoo feathers that acknowledge belonging from the distance of half a world away.

Two poems were selected as runners-up, both equal in their qualities in the judges’ eyes.

Emilie Collyer’s ‘Lateral ambling gait’ is a clear-eyed poem that weaves multiple stories together in understated quatrains. The speaker’s own ‘bone density report’ on the progress of ‘AP spine Osteopenia’ and its effects on her life are placed alongside the funeral of the speaker’s aunt, recounting the speed with which ‘Cancer galloped through/ my aunt, a few weeks from/ indigestion to death’. Alongside these dual stories, the image of a small horse – ‘inside/ my uncle’s chest’, or metaphor for the speaker’s ‘eager to please’ manner – examines the ‘Lateral ambling gait’ of the title. The poem is urgent and unyielding, accomplished and understated.

Helen Jarvis’ ‘and’ uses its form to brilliant effect: the white space down the centre of the page around which the poem centres both resembles the ‘espaliered’ fig tree glimpsed in the poem and recalls the act of type-setting, an action once done in reverse, a mirror image to the text appearing on the page. This poem takes the reader on a drive through varied landscapes – a rainbow, the ‘rubble beside/ the new McDonald’s’, down an alley flushed with ‘May blossom’ – and through the years, both of the speaker’s life and ‘down five centuries’ of punch-cutter’s work. The ‘and’/ ‘&’ of the title and end-title of the poem speak to the act of linking, accumulation – and to the way that, as the poet states, ‘Life finds/ ways to commit to you’.

The breadth of the poems we read through the different stages of this competition reflected a contemporary Australian poetry landscape that offers a rich chorus of voices. We are delighted to be able to present a comprehensive shortlist that showcases such range and versatility. From family photographs to flooded houses, from algae to black holes, the poems on this shortlist show the sheer variety of subjects upon which poems can be made, and that can remake us as readers.

— Kate Middleton, Poetry Editor

This issue marks my first stint as nonfiction editor. Island was an early supporter of my own work and, in large part thanks to the editorial team, afforded me some of those first, crucial publications. I must thank my powerhouse predecessor, Anna Spargo-Ryan, for what she brought to the magazine’s literary culture – the quality of submissions surely speaks to her ongoing influence. The pieces I’ve selected offer playful, wry and vivid observations of bodies in place. Some of those bodies are human and some are not. Some of those places are called ‘home’, though the safety and security of that realm is variously put into question. Quite inadvertently, there is a strong avian theme for which I do not apologise.

In ‘Treading water’, Marlene Baquiran examines her relationship with water and her allegiances concerning climate justice. Zowie Douglas-Kinghorn comes face-to-face with an underfunded and overwrought aged-care system in ‘Life cycles’. ‘To Penny’ is Kathleen Williams’ deeply personal meditation on loss, home, and interspecies love, told with a snortingly funny voice. Gregory Day takes a sceptical look at ornithological research in ‘A choir of shore’, pondering the effect of excessive data on the human capacity for enchantment. And Dani Netherclift offers a literal break in form with ‘50 fragments’, which depicts a life in shards, revering the slivers that make the whole.

— Keely Jobe, Nonfiction Editor

Summer is gone and the arbitrary significance of the new calendar year is receding. The stories I’ve chosen for this issue echo (for me, at least) this funny, transitional time of year, centring on themes of yearning, anxiety and the brightness of hope. In Gan Ainm’s incisive and politically engaged ‘The Mainlanders’, a Tasmanian baggage handler wrestles with his place in a changing and changed landscape, and in Yiwei Chai’s elegantly subtle ‘The pond’, a woman seeks something both specific and intangible in her own back garden. Indigo Bailey zooms from the intimate to the galactic and back again in her hopeful story ‘Namesake’, while Edmario Lesi explores true friendship and longing in an indifferent world in his delicate ‘Bending light’. Meanwhile, in the enigmatic ‘Mycelium’, Sarah Walker shows us the minutiae of a lonely life being redirected in – and into – a strange, dark place.

— Kate Kruimink, Fiction Editor

The arts features in Island 170 read like a portrait of a moment. In one corner we have a series of YES posters made with burgeoning hope that Australia would wedge open a dedicated space for the voice of First Peoples across Australia. While that referendum vote was not the vehicle many had hoped, the works created by Raymond Arnold, Leigh Rigozzi and Tony Thorne are worthy of celebration and capture within the Island archive. They have rendered that instant in ink.

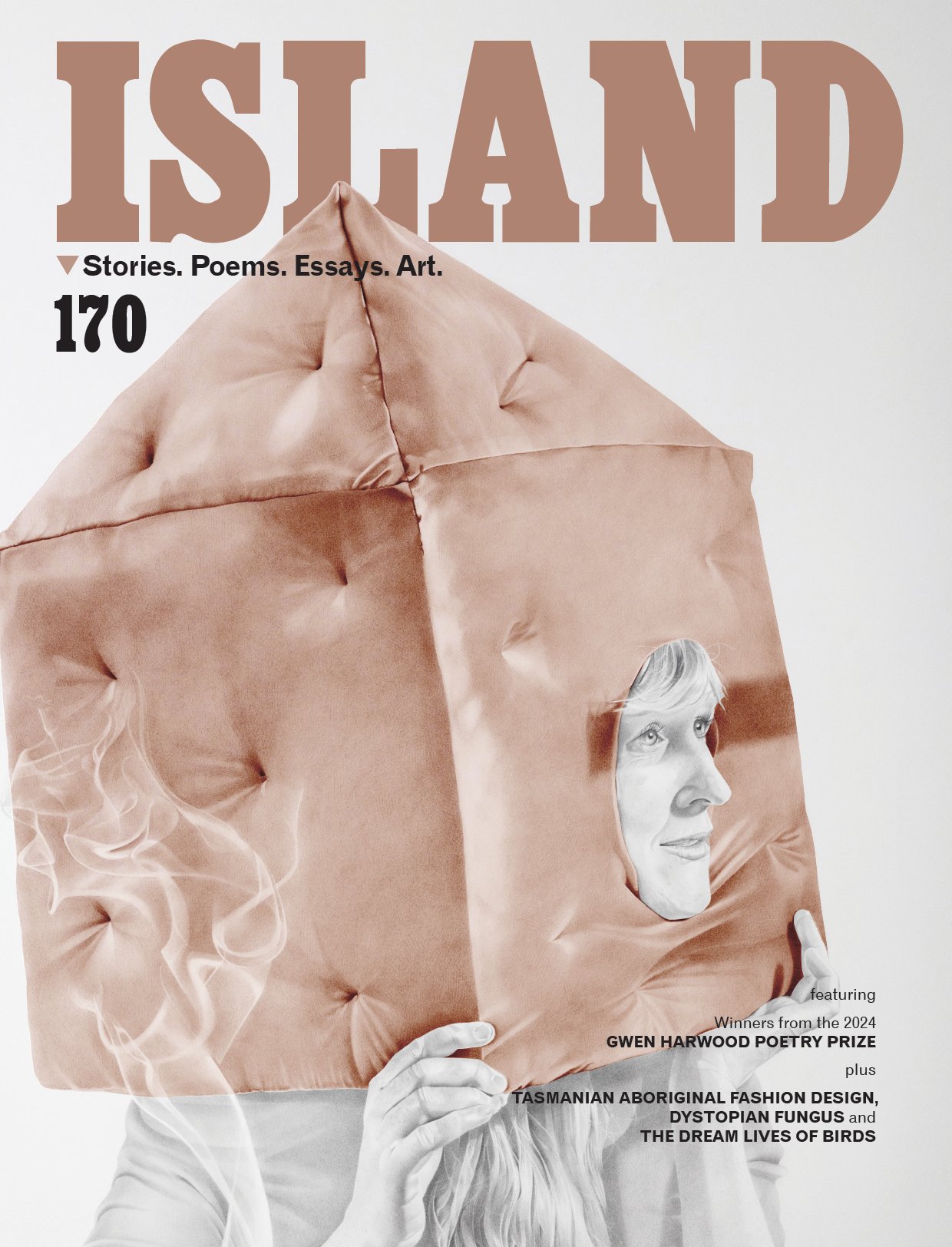

In another corner we have the delicate, tremulous and somewhat astonishing pencil drawings of Helen Goninon. She describes how she is trying to articulate a feeling many of us experience – a low rumble of anxiety for a world within which we have maximum observation, yet limited agency to affect change.

And the last of our features reveals a vein of creativity, determination and community that also lives in this moment. Denise Robinson relates the experience of attending the moving launch event for Silk Stockings at the Babel Island Store at Design Tasmania, where Michelle Maynard, Lillian Wheatley and Takira Simon-Brown presented their collections of Tasmanian First Nations fashion. Together, they form a bittersweet likeness.

— Judith Abell, Arts Features Editor