A Shadow From Country – by Naomi Parry

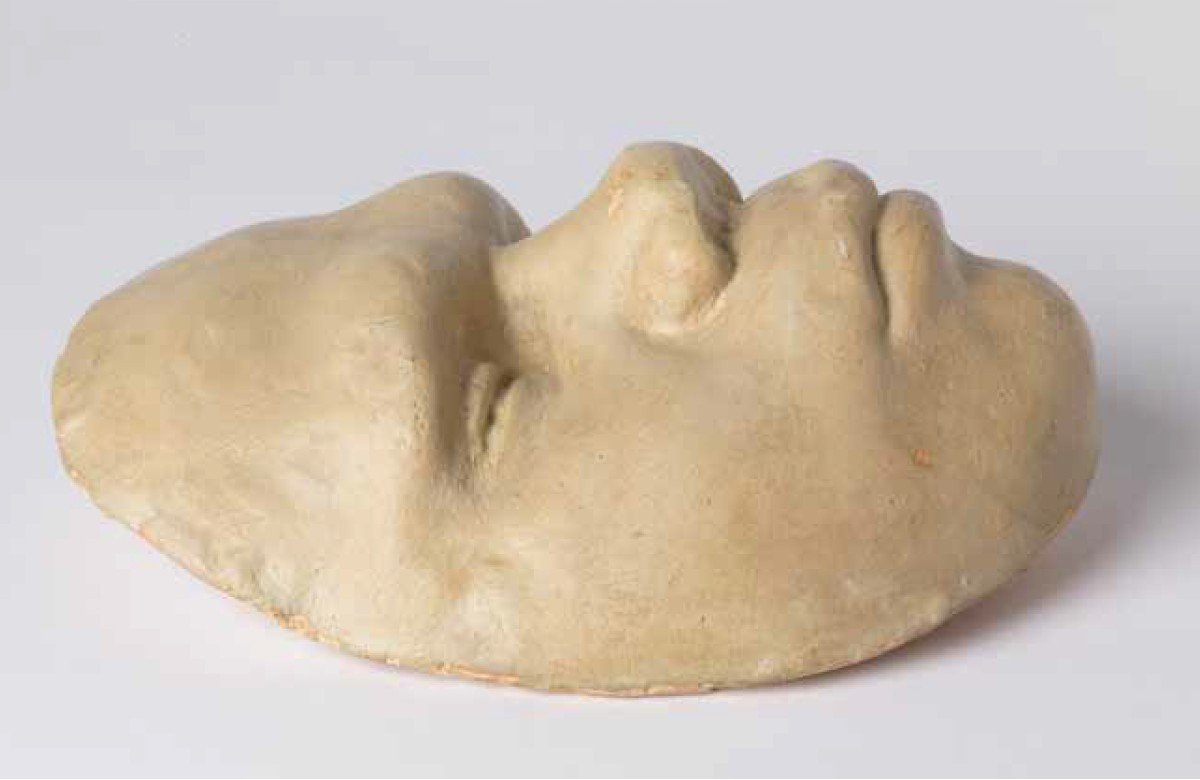

ISLAND | ISSUE 162I am sitting in an office in the State Library of New South Wales with my friend Melissa Jackson, a Bundjalung woman and Indigenous Librarian. It’s a sunny January afternoon in 2021 and it’s her first day back in the library after the COVID-19 closures hit the previous March. I’ve been researching the Gai-mariagal warrior Musquito since 2003 and today we are looking for a name list that I have heard about, which is supposed to tell a story of the time he was exiled from Sydney to Norfolk Island. We go through indexes and bibliographies and footnotes without finding anything. Then Melissa flicks through the computer catalogue and pulls up an image. It’s a seraphic face, illuminated in the computer’s glow.

Who is this?

It’s Black Jack. It’s his death mask.

Time telescopes two centuries to another summer day, 25 February 1825, the day this palawa man was hanged from a mighty beam above the walls of Hobart Gaol, alongside Musquito and six convicts from England and Ireland. I have touched the beam from which they swung, for it was moved to the Campbell Street Gaol in the 1830s and is part of the Hobart Penitentiary Chapel museum, but I did not expect to see an artefact like this. I did not expect to see the face of the man who lived and died alongside Musquito.

Death masks are not human remains but they are formed from them. Helen McDonald has written in Possessing the Dead that it is best to make them when a body is fresh, lest blood pool and distort the features. The maker greases the skin, then delicately covers the face with bandages soaked in plaster. When the bandages dry they form a shell that the maker detaches. This is the negative, a shadow, just one remove from life. The maker fills the negative with plaster or wax or bronze and creates the positive. The positive is what becomes the mask, although it is really two steps from life: a copy, a shadow of a shadow.

“The positive is what becomes the mask, although it is really two steps from life: a copy, a shadow of a shadow.”

And yet there is so much in those shadows. When I see this mask I realise that someone took Black Jack down from the gallows and with their hands smoothed plaster sheets over his face to make the mould for this mask. And here it is, in the State Library of New South Wales. The catalogue says it has been there since 1952. I have been tracing Musquito in the archives for nearly 20 years and I missed this. So has every other historian of Musquito, and the Black War.

I reach for Melissa’s hand and we look at this beautiful face through the computer screen and it’s impossible not to cry.

He’s just a boy. A beautiful Aboriginal boy.

*

Until that moment I had barely thought about what the colonial authorities did with the bodies of Musquito and Black Jack. I had always been more interested in the symbol Governor George Arthur created by hanging them. Black Jack is a quieter presence in the archive than Musquito, but here he is, and if there is a death mask of one, is there not a mask of the other? And what happened to their bodies?

“Black Jack is a quieter presence in the archive than Musquito, but here he is, and if there is a death mask of one, is there not a mask of the other? And what happened to their bodies?”

The words ‘Black Jack executed for murder 1825 J Scott’ are scrawled in the plaster on the back of the mask. In the Mitchell Library card catalogue I read that J Scott was a Royal Navy surgeon, stationed in Hobart. He must have been present at the hangings and certified the deaths of the eight men before taking charge of their corpses. The death mask he made was an act of preservation, but most likely just the first of a series of processes Scott applied to the body of Black Jack and, we can be sure, to Musquito.

For Scott was a persevering anatomist and assiduous dissector of convict bodies, as Helen McDonald revealed in Human Remains. Her Possessing the Dead explains that the right to dissect the bodies of hanged men was a privilege granted to British doctors under the English Murder Act of 1752. When anatomists exhausted the supplies from the gallows, tempting the grave-robbing resurrectionists, the authorities handed over the bodies of those who died in workhouses and hospitals and jails. McDonald says the prisoners on board the hulks in the Thames feared they were being allowed to die in order to provide more bodies for dissection.

Most of the convicts of Hobart Town who watched the hangings on 25 February 1825 had been on those hulks and understood only too well what was likely to happen afterwards. These are the people from whom I am descended, and seeing Black Jack’s death mask has woken me up to what they knew.

I should have understood this before now, for I have been writing about how Musquito came to be taken from Sydney and sent to Norfolk Island and Van Diemen’s Land since I prepared his entry for the Australian Dictionary of Biography in 2005. Musquito spoke into the colonists’ records for much of his adult life, beginning in 1802, when he met French explorers in Sydney and, as my friend Kristyn Harman has convinced me, sat for a portrait under the name Y-err-an-gou-la-ga. He became active in the Sydney Wars in the Darug country of the Hawkesbury, and when he was jailed in Parramatta he threatened to set it on fire. He was exiled to Norfolk Island in 1805 and – perhaps – gave Irish rebel Reverend Henry Fulton a word list. When Norfolk Island was evacuated to Port Dalrymple in 1813, Musquito asked to go home but was denied because he was a useful tracker. He left white settlement and eventually joined the Tame Gang. These were palawa who were dislocated from their people and country, many stolen as children and raised in white households, who had chosen to live their own way. And around 1823, Musquito joined with the Oyster Bay People, the paredarerme.

Musquito’s life in Sydney and on Norfolk Island meant he was well known to the whites of Van Diemen’s Land, and the colonists blamed him for an upsurge in violence around Hobart. There is no story about Black Jack’s people or his proper name, but it seems he was with Musquito and the paredarerme at a critical moment. In November 1823 they happened across three stockkeepers who had built a hut and monopolised the fresh water at Grindstone Bay, laremairremener Country. At first, relations were cordial, but something shifted in the conversations around that hut, and a stockkeeper called William Holyoak and a Tahitian man called Mammoa were killed. The sole survivor, John Radford, got word to his employers and Musquito and Black Jack became wanted men.

After months on the run, Musquito was caught by a youth named Tegg or Teague, who had also been stolen, possibly from the Darug. Musquito was sent to trial for the murder of William Holyoak in the Hobart Supreme Court and the Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser of 3 December 1824 reported that Radford described Musquito at length and confirmed that Black Jack was with the mob:

I know Black Jack very well by his figure, and because his lips are much thinner than those of the natives in general. … On being spoken to, he answered me in English quite well. I never heard the prisoner called ‘Black Jack,’ but simply ‘Jack.’ I call him Black Jack from his colour.

Musquito alone was found to be responsible for Holyoak’s death and he and Black Jack were exonerated of Mammoa’s, but Black Jack was kept in jail and tried again on 21 January 1825 as principal in the second degree for the murder of a stockkeeper called ‘Macarty’ or ‘Macarthy’. Black Jack pleaded not guilty but it was to no avail. This was the beginning of Arthur’s administration and he was cracking down on the behaviour of everyone in the settlement, black and white.

The Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser went to press on the afternoon of 25 February 1825 with the story of the hangings and explained the example that Arthur intended to set:

This morning Henry McConnell, for bush-ranging and burglary; James Bryan, Jeremiah Ryan, Charles Ryder, Musquito, a Sydney black, and Black Jack, a native of this Colony for murder, John Logan, for shooting with intent to murder Mr. Shoobridge and Peter Thackery, for stealing in a dwelling-house, and putting the owner in bodily fear, were executed according to their sentence—a sad example of the fate which sooner or later must overtake the enormities of which they had been convicted …

The men sang hymns and then Reverend William Bedford stepped forward:

My dear Friends—It is the anxious wish of these our dying fellow sinners, that I should thus in public, acknowledge for them the justice of their condemnation, and that I should call upon you to repent, “for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” They implore you to take warning from their ignominious end; they entreat in this their last hour that you will turn from the error of your ways to the Lord your GOD, for he will have mercy. Yes, my brethren, these poor unhappy fellow-worms whose lives have become forfeited to the laws of violated justice and humanity, implore you all to shun the path that leads to death—to avoid bad company—to be industrious, sober, and slow to anger—to be obedient, honest, and religious. May their prayers be answered, may their fate be impressed with salutary force on your Recollection, and may you now successfully join me and them in cries to the Redeemer for their, pardon in another world.

At that point the men were said to be launched into eternity, but to what Christian eternity could a palawa man and a Gai-mariagal man hope for? Had Musquito and Black Jack really pleased Bedford and the onlookers with a show of remorse and sung the hymns? There is nothing to say they did not. But while the six white men are listed in the 1825 Burial Register of St David’s Cemetery, Musquito and Black Jack’s names do not appear alongside them, or at all.

The following year two Aboriginal men, Jack and Dick, were hanged for murdering a stockman who had flogged them. They do appear in the burial register but it notes ‘ceremony not performed’. The Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser of 22 September 1826 initially reported that they received the sacrament from the hands of the Rev. Ordinary of the Gaol (Bedford), but in the next issue of 12 October it recanted, ‘and we need not trouble our readers with any reasons why they did not.’

So Jack and Dick were buried in St David’s, but not in consecrated ground. Whether consecrated or not, the cemetery was in a parlous state: unfenced, with coffins emerging from the ground and nibbled on by pigs. One wonders how long Jack and Dick rested there. Today the headstones in St David’s have been tidied against the walls to make a peaceful park. There is a monument that mentions Musquito as one of the Norfolk Islanders, but nothing to suggest that Aboriginal people were laid in that place, however momentarily.

“Today the headstones in St David’s have been tidied against the walls to make a peaceful park. There is a monument that mentions Musquito as one of the Norfolk Islanders, but nothing to suggest that Aboriginal people were laid in that place, however momentarily.”

The archive reveals one more small fact about Black Jack’s life. In January 1827 the Colonial Times tabulated the extent of Arthur’s killing spree and named more than 70 men who were hanged in Hobart. Black Jack was listed under the name Jack Roberts. This application of an English name tells us Black Jack was not only known to the colonists, but that he almost certainly grew up in a white household, as a servant. He was one of those stolen children who shocked the colonists by leaving ‘civilisation’ to reclaim an Aboriginal life – one of those who returned to Country.

I hope the story of this mask, and of how it came to be in New South Wales, might take me to these long-lost bodies. The voluminous records of the business dealings of the State Library of New South Wales offer no clues, just a catalogue entry from 1952. But the Mitchell Library holds many of the papers of Tasmanian surveyor and writer James Erskine Calder, who in late 1876, just a few months after Trucanini’s death, responded to a request from SW Silver, a colonial outfitter and editor of his family firm’s newsletter The Colonies, for information and ‘economic specimens’ relevant to the British Empire. Calder said he had little more than a fossil bone and some amber, but:

I have also a plaster cast of the face of one of the four aboriginals who were executed for murder in 1825–26 [on the 25th of Feby 1825]. See page 46th of the pamphlet sent you also which I could give you if they are worth having. … The [plaster] cast of the Aboriginal was taken after death by the [“Colonial Surgeon” that is the] chief of the Medical Staff of the time, Dr Scott of the Royal Navy.

This must be Black Jack’s death mask. There is no sign Silver accepted it, so it probably remained with Calder and was bundled up with his papers when they were acquired by David Scott Mitchell. It’s unclear where Calder got it – he was a gregarious man who knew many people in Tasmania, including descendants of Dr James Scott – but he almost certainly had it while he wrote Some account of the wars, extirpation, habits, &c., of the native tribes of Tasmania and wrote his lists of Aboriginal languages. That he could speak of the mask without naming the person who once inhabited the form tells us much about what he thought about Aboriginal people.

So the mask has a provenance, but what happened to Musquito and Black Jack’s bodies? I find myself trawling through the Mitchell Library and the Tasmanian Archives and the University of Tasmania’s Rare Books Collection and letters and diaries, looking for names. Isn’t that always the dream of the archive, that it will turn up a piece of paper that will tell you the story you seek? But the people who created archives rarely made them with you in mind. They had their own reasons and their own lists. Those who created museum collections packaged up skulls and bones and skeletons without any sort of story but the craniologists did want those stories, if only to match them with their measurements and opinions, so it’s to them I turn. It’s nauseating, and the only thing that keeps me going is the hope of catching sight of Musquito and Black Jack.

“Those who created museum collections packaged up skulls and bones and skeletons without any sort of story but the craniologists did want those stories, if only to match them with their measurements and opinions, so it’s to them I turn. It’s nauseating, and the only thing that keeps me going is the hope of catching sight of Musquito and Black Jack.”

Looking into the lists of the craniologists brings stories of other lost people, so many of them. Dr Joseph Barnard Davis’s Thesaurus Craniorum is a catalogue of the skulls he had in his collection in Staffordshire. Barnard Davis was an equal opportunity collector, as devoted to gathering British and European skulls from across the aeons as he was to collecting those from across the globe. He did care about provenance and named skulls if he could, while recording damning information about those who sent them to him. The Thesaurus contains stories of English convicts, Jewish soldiers, Laplanders, and a Hindu woman who was buried alive with her deceased husband in desert sands but was excavated by a British priest as a gift for his wife. So many ignoble collectors. In his section on ‘Australian Races’, Barnard Davis described 24 skulls from South Australia, Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales, often sold to him by government departments and officers. Some have names – ‘Carbon Will’ from Moreton Bay, who speared Commandant Logan, and ‘Malgoey Bob’ from Sydney.

Barnard Davis bought George Augustus Robinson’s collection of artefacts and remains. In all he had ten skulls of the ‘Tasmanian Race’ (for he considered them a separate people). Some were sold to him by illustrious Tasmanians like John Skinner Prout, and Dr Joseph Milligan, Protector of Aborigines. One skull was that of a 35-year-old man ‘who was considered to have murdered two shepherds attached to the family of Mr ESPIE, Surgeon, and was at last shot by one of their overseers. It was presented to DEVILLE by Mr. ESPIE.’

This last skull had been exposed to fire but subsequently buried, which led Barnard Davis to an aside:

It was a practice amongst almost all the tribes of Tasmania to burn the dead, which renders their remains so scarce. Even where the body was not at once purposely burned, the result was the same; for a chief’s body, if it may be said that they had chiefs, was sometimes placed in a hollow tree in a standing position, with a number of spears and clubs put beside it, and the opening closed up; or the body was doubled up and placed on its haunches, and wood piled round it as a protection. In both cases the first bush-fire destroyed the human remains. This is one of the finest examples in any collection of a cranium of a people so nearly extinct …

The colonists who sold bones to Barnard Davis talked of finding skulls and bones loose on the ground, which may have been a politeness to avoid accusations of graverobbing, but Barnard Davis’s continual descriptions of pieces as ‘weathered’ speaks to a desolate dying, alone and untended, while the British swept through lutruwita. There was no one to burn these bodies or, after the palawa had accepted Christian burial ways, to lay them in the ground.

Barnard Davis wrote in the full knowledge of the dispossession of the palawa but he truly believed that describing the relics of the Tasmanian ‘man’ provided ‘him’ with permanence of record in illustrious European scientific volumes. He seems not to have noticed the terrible irony that he, like most other anatomists, measured the capacity of the skulls of Tasmanians by filling them with lead shot.

And fire eventually came for Barnard Davis’s collection. His family sold it to the Royal College of Surgeons in London after his death, but that institution disappeared under German bombs on 10 May 1941. Surviving catalogues in French and German that were once surveyed by NJB Plomley provide hints at what is lost, but there is so far nothing that ties to Musquito or Black Jack.

Of course, not all palawa who were stolen from Country left the island. In the Royal Society Papers I read that Joshua John Hayes, a third-generation settler who served as the Member for Brighton in the Tasmanian Parliament told his daughter in 1882 that Musquito’s cranium was ‘in our museum’. It may once have been, though my trawlwoolway friend Tony Brown, formerly the Senior Curator of Indigenous Cultures at the Tasmanian Museum, is confident it is not there now. Perhaps it was labelled after the fashion of Barnard Davis as ‘Australian’ and is now anonymous, or was sent elsewhere, or was never labelled at all. Even the Tasmanians in the collection were barely named and little understood. In 1920, W Lodewyk Crowther DSO MB (son of the mutilator of William Lanne) wrote a paper for the Royal Society with Clive E Lord of the Tasmanian Museum. They described the skulls and bones in the museum’s collection as ‘the largest single collection of osteological remains of the extinct Tasmanian aboriginal race’, but admitted most had never been described. Only three had names: Augustus, Caroline and Trucanini.

This despicable ‘scientific’ racism survived a long time. NJB Plomley, a well-known historian of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and compiler of the papers of George Augustus Robinson, was wistful about the state of the physical fragments of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people, but not for the reasons one might expect. He himself was an anatomist and craniologist. While his work has been invaluable in repatriation and his word lists guide the reconstruction of the palawa kani language, he firmly believed Tasmanians were extinct. His lists were not written to return bodies and objects to Country, but to make a case for their examination and even for gaining more body parts. In 1965 Plomley lamented in Records of the Queen Victoria Museum that surviving osteological collections were scant and poorly provenanced. His attitude is chilling:

A major disadvantage in work on the skull (and skeleton) in the Tasmanians is the small amount of material available for study. Attention might be directed to the possibility of obtaining more by excavation of graves of known fullbloods, both in Tasmania and on the islands of Bass Strait.

I am grateful that shortly after Plomley wrote these words, the tide of history turned against the anatomists and the craniologists and the palawa have been able to reclaim many of their ancestors and lay them to rest. In 2019, the University of Tasmania apologised to the palawa and in early 2021 the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery and the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery also apologised. Most of the bodies and sacred artefacts they hoarded have been returned. And palawa are mining the works of Plomley and Calder to roll the place names back across the country. But there is still so much missing.

*

A few weeks after Melissa shows me the computer entry for the mask of Black Jack I make an appointment with State Library staff to sit with it. It rests in an archival box, fitted with a custom-made cushion. He is a beautiful boy, so young, maybe 20. The word Melissa uses is gracile. There is no beard or eyebrows or lashes – perhaps the plaster mould pulled them away, perhaps his face was shaved. There are no scars upon it. And it is small. I put my wrists together and spread my hands out to make a cup that fits perfectly around the bowl of his chin and my middle fingers reach to his temples. Then I put my hands under my own chin and touch my temples. I am a small person and this mask is exactly the same size as my face.

It is a powerful object, inspirited. Black Jack’s eyes are not fully lidded shut. It seems his blood still runs close to the surface and his muscles still animate his lips and cheeks. There is none of the disfiguring swelling and pooling of blood around the neck and jaw that State Library curator Rachel Franks tells me usually occurs in hangings. Black Jack’s life seems one breath away. And there is nothing on his face that reveals the fear Arthur might have hoped for, or the repentance Bedford tried to extract. It’s the face of a defiant young man. It’s a warrior’s face. He looks proud.

“Black Jack’s life seems one breath away. And there is nothing on his face that reveals the fear Arthur might have hoped for, or the repentance Bedford tried to extract. It’s the face of a defiant young man. It’s a warrior’s face. He looks proud.”

There is also a story hidden in the way this object was made. Its surface has been painted with a khaki wash and the brush strokes of the unknown artist obscure some details, such as a small broken section at the tip of the nose. There are chips in this paint, and they show the mask is made of unfired clay. Clay is not a typical substance for death masks but the colour is familiar to me, because it’s the soft red ochre of the sandstock bricks that fill the streets of old Hobart Town.

Tony Birch has written about how urban development moves soils from Aboriginal Country to elsewhere and this serves as a ‘masking agent for a history of colonial destruction’ of Aboriginal cultural and scientific knowledge. The word for the act of returning Aboriginal remains and cultural artefacts to their community is repatriation. It means being restored to one’s own country and it’s the same word military authorities use to talk about the process of bringing home war dead. In a nation that does not acknowledge that colonists and palawa were engaged in warfare, the double meaning of the word repatriation has a particular power. The maker of this mask pressed little pieces of Country into the shadows in the mould of Black Jack’s face, intending to document destruction. Instead they wrought a story of Country and the wars fought to protect it, and the warriors who proudly died for it. ▼

Images of Black Jack’s death mask courtesy of the Mitchell Library,

State Library of NSW, [SAFE/DR 4]

This essay appeared in Island 162 in 2021. Order a print issue here.

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.