Fury - by Andrew Harper, on Lucienne Rickard’s ‘Extinction Studies’

ISLAND | issue 159Image courtesy of Detached Cultural Organisation and Jesse Hunniford

Image courtesy of Detached Cultural Organisation and Jesse Hunniford

Text by Andrew Harper

Come and see.

Lucienne Rickard is doing something extraordinary in the TMAG foyer. She is doing the same thing, over and over again, and she has been doing it since September 2019, before the fires on mainland Australia drew the attention of the world and filled us with a long dread about what is to come and what is here already.

The resonance of these disparate elements dawned on me as I visited Lucienne, again, to watch her draw. That’s what she is doing, again and again: drawing.

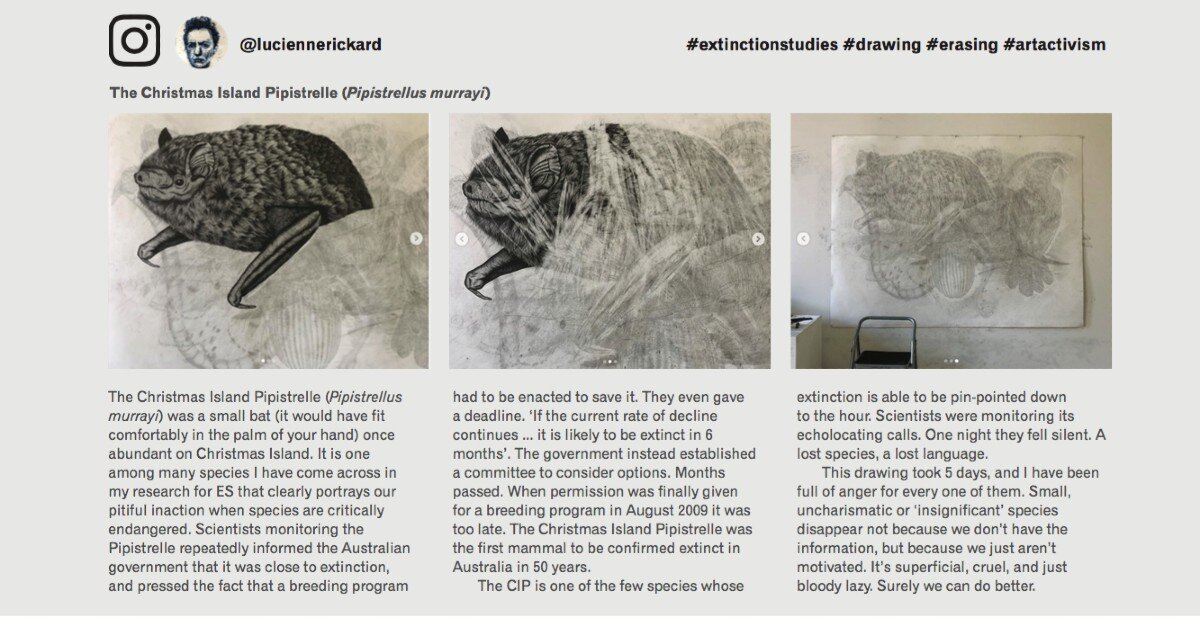

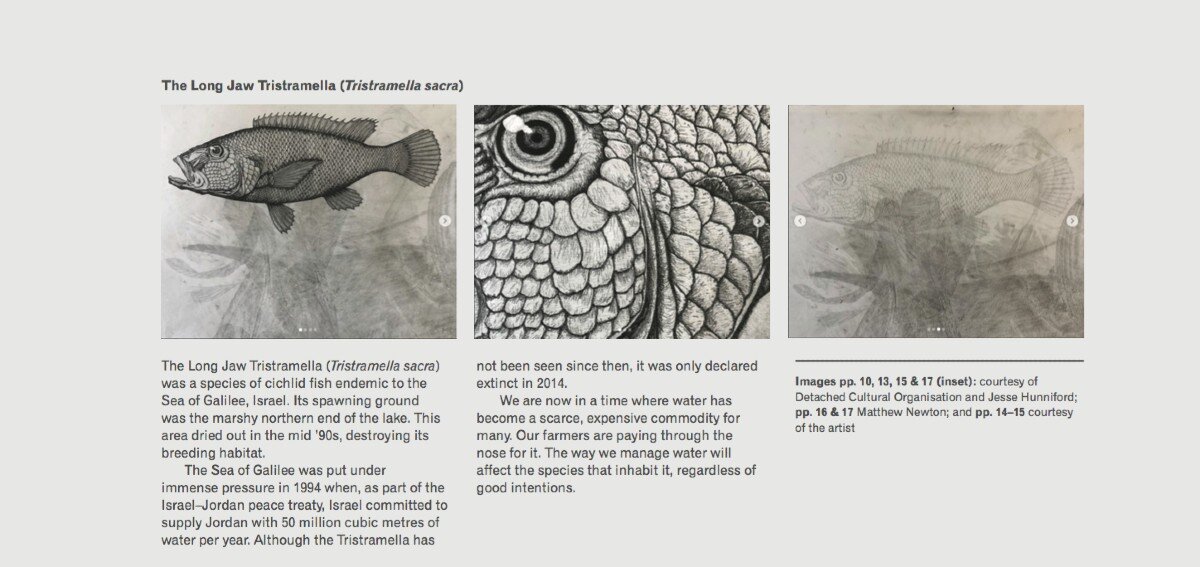

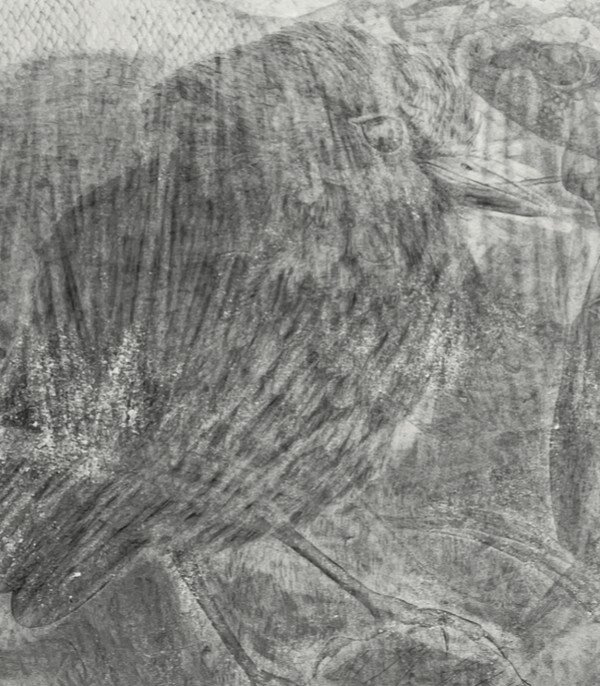

She’s drawing dead things. She is making a long artwork called Extinction Studies.

Lucienne has been doing insanely delicate, detailed, obsessive drawings for as long as I’ve known her. She has always drawn bodies: animals, people. Her work is beyond intricate: it is dark, heavy, intense and intensive. She draws with pencil, and she goes through many, many pencils, with an intimate understanding of the correct pressure required to produce the right line, the curve, the grain of what she is drawing.

You can go and watch her draw, in the TMAG foyer. She is focused and driven. It is very beautiful to watch a human do a thing they are good at. Work like this – hard work – to make something a human believes in, to the best of their ability – is extraordinary to see.

*

Lucienne is drawing extinct things.

She has drawn a fly. A skink. A turtle.

She draws them incredibly well. She puts effort in. She does her work and uses her ability and her skill and I think she’s trying to honour these things. Because as she draws, she looks at images of these now-extinct, now-dead, now-gone creatures, and she wonders about them, seeing how well they had evolved to be the commonplace miracles that every living creature is. She looks at the detail, and sees the detail, and draws it. Until the drawing is finished.

Then she takes an eraser, and rubs it out.

Because it is gone.

Because it is dead.

And because she is furious.

It is the calmest and most focused fury I might ever see: not screaming or violent, but what else would motivate an artist to produce an exquisite, accurate rendering and then erase it. Look, she says, with each gesture of removal. Look what we have done. Look what has gone. Look at what is no longer there.

I think Lucienne is sad, and worried, and furious.

*

Extinction Studies is a durational performance artwork that takes place over a year. It’s not an artist drawing something and then erasing it. The work is not about any individual drawing; it is about the work of making the drawings, which allows the artist to lean into the now-extinct lifeform she is drawing and thus see it, and wonder at what it was, and mourn that it is gone, and – to stop ‘her magical sad drawing’ being fetishised as a desirable object within a capitalist system that destroyed the entity she draws – to erase it.

It is an artist using her skill set and her understanding of art to symbolically bring the reality of mass extinction directly to people for whom the idea of extinction is distant and abstract.

Apparently people sometimes get angry at Lucienne for rubbing the drawings out, and well they might, because that act undermines the way that many people understand art, as objects to be bought and sold. This is not about the end product. There is no end product. There’s just work.

“This is not about the end product. There is no end product. There’s just work.”

This is an artist working: working like we all do, because actually, that’s what artists do. An artwork is called a ‘work’ for good reason.

Lucienne has not taken a day off. She is working hard, but she doesn’t really have a choice. There is only so much time.

I think it would be reasonable if she did take a break; this must be emotionally challenging for her. She has said that drawing the now-extinct lifeform has drawn her closer to each one: a bat’s tiny form reveals how meticulously evolution and natural selection has sculpted it.

Bats are astounding. Small dragon-faced wonders with their soft fur, their magic webbed hands, their baffling ears. The way they navigate and hunt with sonar. Their precise ability to pinpoint small prey. The awkward, urgent, funny way they fly.

That bat she drew, the Christmas Island Pipistrelle, is gone. Lucienne drew it large so we could see all the contours of its clever ears.

I loved it.

It made me so sad.

Oh, you night dragon, you barely weighed anything. What harm did you do? None, no harm at all.

Into the long night of extinction, the night with no dawn. Oh, little bat, fly dead through the night with no end forever. You are gone. I am so sorry your stunning, beautiful, frail ears that could hear the flight of an insect are gone. I’m so sorry.

I will tell my sons you were a miracle of nature and time.

I will probably weep.

*

Lucienne has taken to announcing times when a drawing will be erased, so that people can see this in action. I saw her erase her drawing of a golden toad, a drawing that she had worked particularly hard on, drawing detail of the creature’s skin for roughly sixty hours – some ten days of work. There was no fanfare nor announcement but, at a point, Lucienne put down her pencil, picked up her eraser and attacked the image with hard, deliberate actions.

She rubbed out every detail, and this took just over seven minutes.

I captured this on my phone and I watch it again and again. I have studied her action and intensity and at no point does she falter. She does not hesitate.

The action of erasing is the critical step.

When I saw this live, I was incredibly surprised by my own reaction. I felt tears form, though I did not quite cry. This made sense: the sight of an artist erasing her own work is harrowing. The symbolism is very direct and brings the point home sharply. In that moment, I saw art being very powerful, really reaching out and seizing the minds of the people watching. They applauded, and that was weird, but it was also the right thing to do, because Lucienne is by herself up there, and while no one made her do it, and while she probably needs to do it, it must hurt her on some level.

But the sting is important too. Because in that moment, we all knew she was drawing the extinction of the golden toad, and making it real for us, and tragic.

And then the next day she did it again, and she is still doing it, adding to her list of astonishing creatures that have been driven into the void by capitalism, by colonialism, by the voracious devouring cannibalism of humanity.

As Lucienne has worked, she has drawn and erased, again and again, on a single sheet of paper. The shallow ghosts of each drawing are still there, left as a faint but definite residue. Each drawing adds to the catalogue of extinction, which has slowly become symbolic of an interconnected ecosystem, damaged and vanishing. This may not have been intentional, but it indicates something critical about Extinction Studies: it began with an idea, and the artist has done her best to follow the course she set for herself, but the work itself has grown and changed. This is the nature of performance art: it is an experiment. The artist takes action and finds out what that action brings.

This continued action, taking place every day, has generated discussion, emotion, ideas and attention. It has not ended, and so we cannot say that this project has succeeded or failed just yet, and perhaps it will do neither, or both – art will not change the world, or save it, but that was never the goal, and all the artist wanted to do was something more than lie down and weep or become paralysed with unproductive rage. She did what an artist does, which is follow her idea through as best she is able, and acknowledge that there is always compromise.

But I think she will get to the end. I think this because people go and watch her rub out the drawings, and they are moved. She is slowly getting more and more attention, and the symbolism is very easy to grasp, but accessibility does not diminish the power of the work.

*

We were talking about endlings. An endling is the last representative of the species. It’s a beautiful, sad, terrible, final word.

We were wondering if the endling would know it was the last.

“We were talking about endlings. An endling is the last representative of the species. It’s a beautiful, sad, terrible, final word.

We were wondering if the endling would know it was the last.”

Lucienne mentioned a rhino, and how she had read that someone suggested that the rhino would not know it was the last of its kind, but she wasn’t sure. I don’t know if the rhino would know it was the last, but I felt certain it would know it was alone.

I went from there, with not much of a leap, to a last human.

No one will draw the last human. Tasked only with mourning, there will be a weight on that slight being so great I cannot dare imagine it.

I am so sorry, one lonely future you.

This is the enormity that Lucienne is trying to draw. Drawing gone. Drawing alone. This is why she’s drawing for a year.

With each image, the work grows, and does not grow, symbolising work without meaning, loss and mourning. There is nothing to see and, in the end, there will be nothing but a list and a series of sheets of paper marred with faint graphite spectres, some jars of pencil shavings and the remains of erasers. All this work for so little, but it is not about the remains. It is about the people who see what has gone, and are moved by it, enraged, saddened, confronted or spurred to action.

All this comes from a wild fury that had to find a channel, a desire to do something that would not be held down by the weight of sadness and loss. Bear witness to the precision of this woman’s anger. Come and see. ▼

Note: The COVID-19 crisis put Lucienne’s work on hold, as TMAG was temporarily closed. Extinction Studies continued, and was live streamed from the museum. Lucienne’s drawings and process could also be experienced via her Instagram feed @luciennerickard. Andrew Harper’s commentary was written before COVID-19. The project was commissioned by Detached Cultural Organisation.

Lucienne Rickard

Lucienne Rickard lives and works in Franklin, Tasmania. She has a BFA from the Queensland College of Art, and a PhD from the University of Tasmania. She received the Rosamond McCulloch Cite Des Arts Paris Residency in 2006, and has been exhibiting nationally for the past 20 years.

This arts feature appeared in Island 159 in 2020. Order a print issue here.

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.