The Backyard Project: Notes from Stolen Land – by Lia Hills

ISLAND | ONLINE ONLY | AUSTRALIAN NATURE WRITINGWurundjeri Country, 2022

murnong

The murnong’s flower head droops, in need of a drink, a single closed tip at the end of an arching stem, like an organic streetlamp or an alien probe. I have no clock with me. I will measure time in plants, one per day, for the week that I’ll spend camping in my backyard – a half-acre in the Dandenongs – off-grid, tech-free, no contact with other humans. The plants come from a community nursery down the road that only sells local indigenous species. Each of the plants I’ll place in this ground has three names: in Latin, English, and Woiwurrung, the language of here. This planting is the only work I have to do, other than eat and drink to keep myself alive, and clear invasive weeds. And think through the question that’s brought me here.

Stuck into the ground near the compost bin is a headless mannequin. My son named it Cassandra and made a short film about it when he was 15: a murder mystery. Now she guards the rotting remains of family meals, her plastic skin impervious to weather. Cassandra, before this is over, I will tell you things I didn’t know I knew.

*

Evening of the first day – red leaves, red clouds, the whole world burnished by celestial rotations. Cicadas take up their electric-charge hum. For the first time in a long while, I wait for the moon to rise. Tech-less – tonight the satellite blinking above me is just another star. The earth is loose and powdery, having been recently cleared. Trees cast moonshadow and above me, invisible bats hold their high-pitched colloquies. I dig a hole and flood it, lower in the murnong by torchlight to avoid damaging the roots. If it takes, the tubers – that vital food source – will spread underground, and there will be more drooping heads to rise up and open into bright suns. Tomorrow, I’ll return with more water, every day until it rains – this autumn warmer than the last, as they will continue to be. But still we plant.

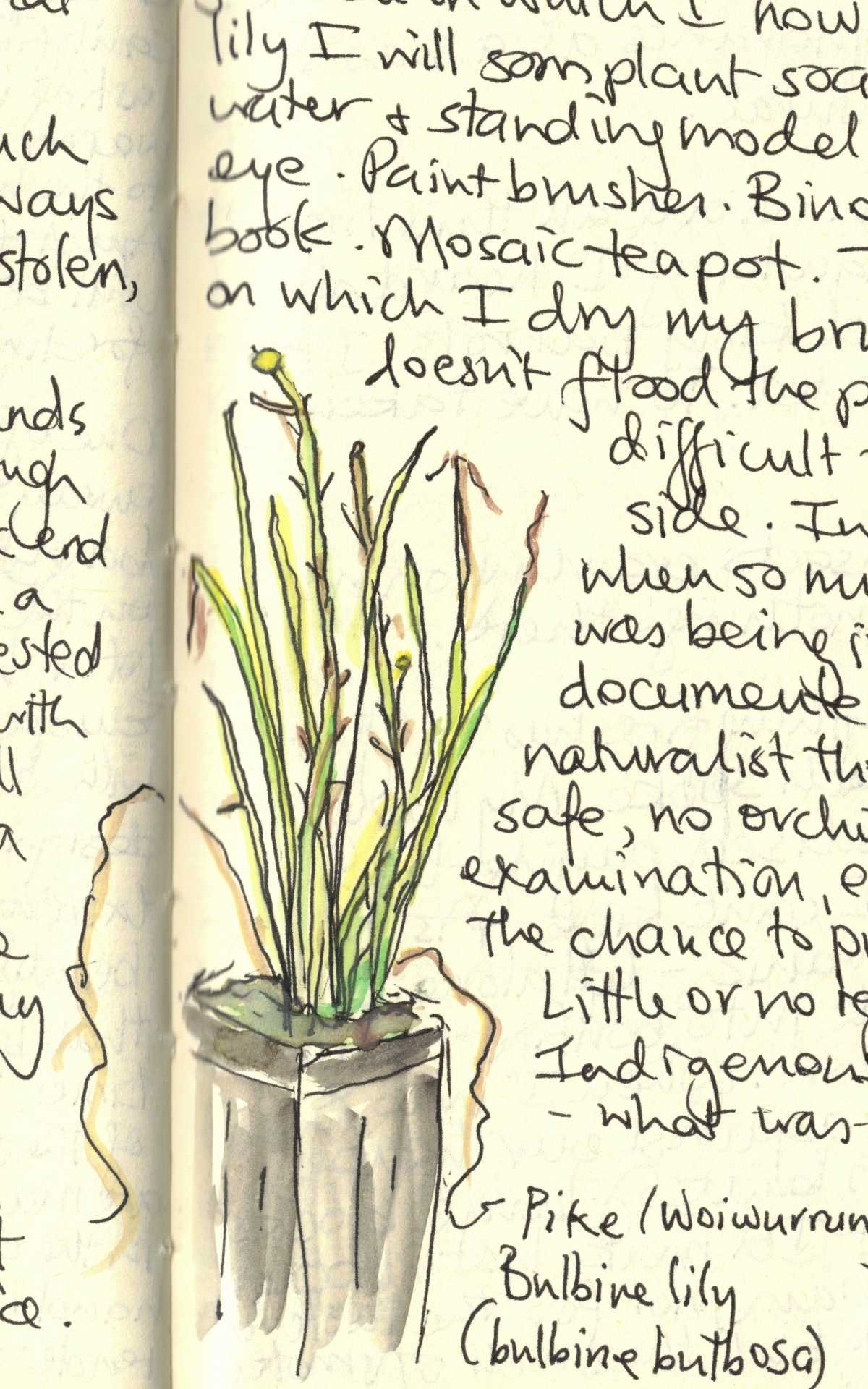

bulbine lily

The tawny frogmouth hooted most insistently in the hour before dawn, when it had to relinquish its territory; then the day-birds began – rosellas, magpies, wattlebirds, currawongs – well before the sun came over the hill. From up there, they see the horizon. Once, we flew a drone over our place; the house was so weather-proofed and angular it felt like a symptom. Over the 23 years I’ve lived here, the birds that share this space have changed; a reminder that birdsong is a signature of time and place. While I wait for the water to boil on the fire, a kookaburra shakes its head violently; there’s the brief spark of a reptile’s belly as its spine is broken and its body swallowed whole. In the grass at my feet, a wasp injects a fly with its poison – a frantic buzzing followed by silence, the working of the mandibles too quiet for my human ears. Slaughter and survival – while down the hill a little, the house begins to wake.

Is this where I’ve come: the no man’s land between human and nonhuman? A no man’s land is supposed to be a place of truce, of passage, but over a decade of travels, whenever I traversed the liminal spaces between countries, newly formed or centuries old, there was always a sense of a bullet waiting for you; of the danger of looking back. A different way of living in place is needed – one that brings an end to the dichotomies that propagate separateness and fear.

Steam bellows from the billy. The kookaburra lets me get close enough to see the scars on its woody beak.

My table near the tent opening looks like it belongs to a naturalist, the kind who took long sea voyages and sent specimens back to Empire: pinned and labelled and classified, and sometimes still alive. Palettes of watercolours. The journal in which I now write. The bulbine lily I’ll plant today standing model for my untrained eye. Paintbrushes. Bird book. Binoculars. In the Victorian era, when so much of this land was being colonised, the amateur naturalist thrived; no butterfly safe, no orchid unworthy of examination, especially if you had the chance to put your name to it. Little or no regard was given to First Nations knowledge systems. Terra nullius – a place void of knowledge, it was assumed. I plant the bulbine lily arm’s length from the murnong. Above them towers the coranderrk bush I grew from a sapling I bought at Belgrave Survival Day, a constant reminder of the Aboriginal reserve (1853-1924) that was named after it. A plant is an act of becoming. I wouldn’t be the first human to place my faith in such precarious things. Never leave your conscience up to the vagaries of the elements, I whisper to the lily, as I smooth the earth.

kangaroo apple

Another beautiful day in outer suburbia, still as a dead man’s lungs. Our place is classified as ‘bushland residential’, which means you’re allowed to burn off what the bush produces. When we bought it, the pyromaniac in me was thrilled. Before I gave thought to the carbon release, I stoked autumn bonfires with pagan ecstasy, singeing hair, parching skin. We classify the land in order to understand it, but also to control; sacrifice large tracts and feel at ease with this, because it’s been designated for this purpose. We are neat in our desecration. But we forgot – forget – that it’s continuous, joined by the elements: water, air, fire.

Later in the morning, I cut down a three-metre mirror bush, an environmental weed. Clinging to it is a wonga vine, a native of this area, with its cream and pink bell-like flowers in abundance for most of summer, though past their flourishing now. If a garden is a metaphor, this one of entanglement is clear. Environmental philosopher Isis Brook points to the desire to ‘feel at home’ influencing our selection of plants, our choices often dictated by childhood experiences. As preparation for this time, I read books and articles about the backyard, both as a real and imaginary place: the tendency to begin with a tabula rasa, removing any trace of ecological or cultural history; the great Australian dream of the quarter-acre plot, the site of the barbecue or backyard cricket; the colonial mentality that leads to a division of natural and cultural heritage, resulting in environmental efforts being focused on nonurban areas. A garden, a backyard, is an unconscious medley of everything you want and everything you can’t let go; an embodiment of your true politics.

I plant a kangaroo apple. If you eat the fruit before it ripens, it can make you sick. To the east, ravens summon the night.

“I plant a kangaroo apple. If you eat the fruit before it ripens, it can make you sick. To the east, ravens summon the night.”

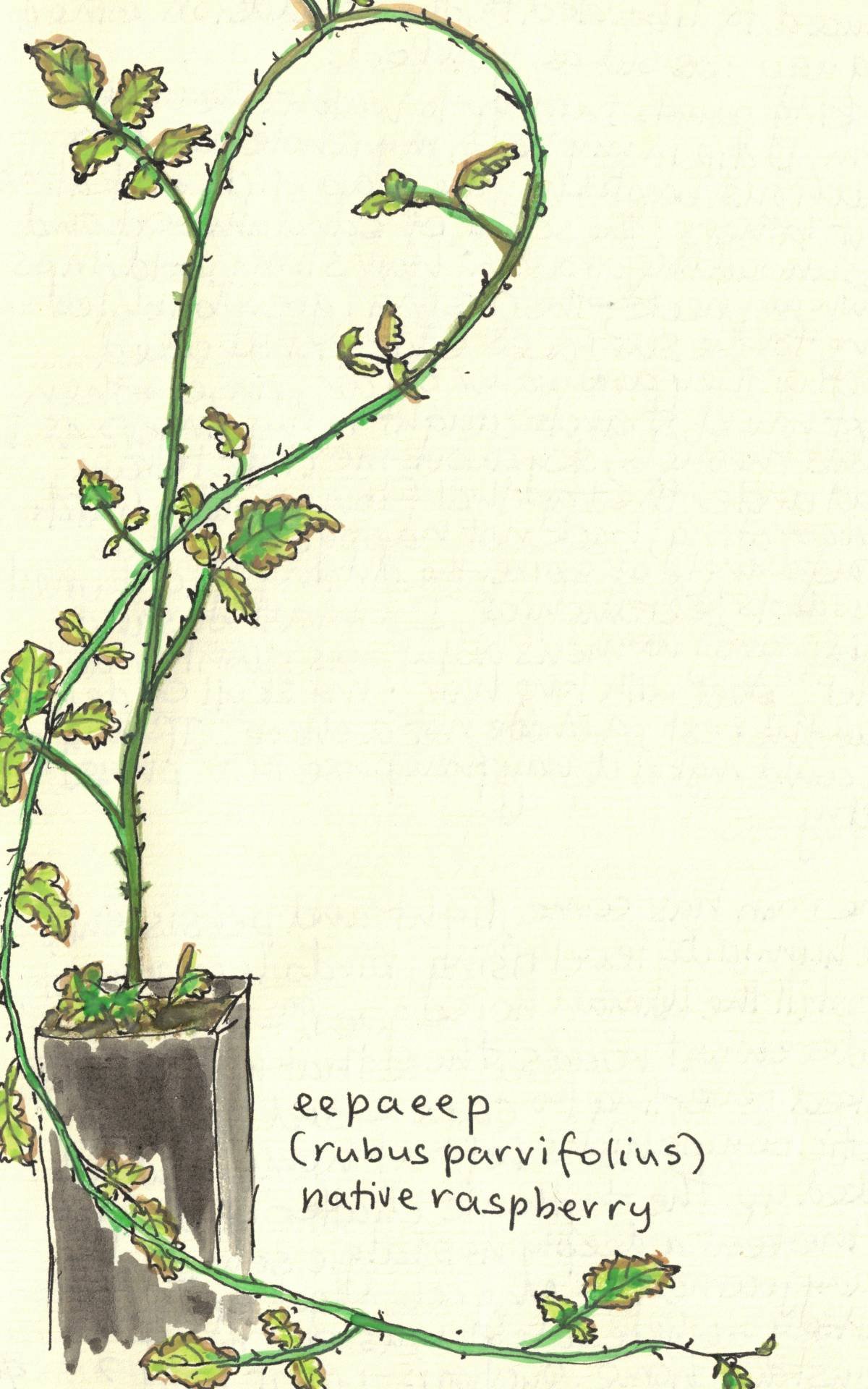

native raspberry

I wake in the half-dark. With no clock, I gauge time by the information at hand. It’s bright enough in the tent to see the outline of everything, though it must be moonlight, as there’s no bird noise. Also, infrequent traffic – and the clearest sign of the hour, no train. From memory, they stop between one and four. Many of us have faculties we rarely use: we glide across the surface, our periphery limited to a small view, neither above in the fly-zone of birds or below amidst the great mycorrhizal networks and the realm of the ants. I say nothing that is new – the novelty is my own, in waking to a night on land I thought I knew. How much I’ve neglected this relationship, made false claims that I was listening, hoped that greater knowledge of this place would be a solution in itself. Can we begin again?

“How much I’ve neglected this relationship, made false claims that I was listening, hoped that greater knowledge of this place would be a solution in itself. Can we begin again?”

It’s surprising how little fuel you need to cook: a small fire reduced to coals, a square of sawn branches to keep the heat. I could cook out here forever with what falls from the trees as they grow taller, those giant carbon extractors. While I wait for the billy to boil, I write on the red hearth bricks with my fire-stick: Lia March 2022. Inscribe your name. Raise a flag. I scratch at the letters and numbers, shake my head at the instinct: ancestral, legal according to the ‘laws of the land’. No matter how hard I scrub, a trace remains.

Rain sets in, so I spend the afternoon reading local histories in my tent. Most describe a story of conquest, the impenetrable bush, early sawmills supplying timber for Melbourne’s exploding population during the Gold Rush, masts for tall ships. Little or no mention is made of Wurundjeri, the traditional and ongoing custodians – history by negation, by neighbourly erasure – not in some elsewhere, but here, where I own title, raise my children, write, love; not far from where Wurundjeri friends and their families live.

There are pictures of the early berry trade, the origin of the blackberry that keeps coming back. The native raspberry, by contrast, is non-invasive. The one I plant beneath the rain will climb this old fence, wrap its tendrils around the wire, push out thorns. And next summer, I’ll collect the small red fruit and remember this week.

chocolate lily

The humidity in the tent is high this morning; the cover of a novel has curled into the letter C. A tiny spider climbs the opposite page of my journal. I pause in my writing to allow its passage. When I began this project, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was in its fourth week. I jokingly told my partner that the only reason to come and get me – apart from a family tragedy – would be if it escalated to nuclear war. Half-jokingly. Call it other things – power, old grievances, the march of history, ideology – but in the end, it’s always about land. And the land and its custodians always suffer.

I sit on my favourite round of wood by the fire. If I had sandpaper, I could sand its surface and expose the rings of the tree well enough to read: a tree as memoir, arborbiography; a monograph of the land from which it grew; ring cycle, gum opera. And we cut it down. Chain-sawed mid-plot. Why? Because it threatened to fall on the neighbour’s house. Since we moved here, four large gums have fallen; a huge messmate leans towards the house. When a big branch drops, you feel the tremor in the earth. We make bargains with nature, and thus with ourselves, when we live amongst such trees.

Tonight I miss the humans. In the lit kitchen at the bottom of the hill, they move as if on a screen, a reality show where I’m related to all the characters but no longer part of the scenario. I build a fire for company and entertainment, an octagon of rippling coals, like a constellation brought to ground. Something is changing in me that I can’t yet name.

“I build a fire for company and entertainment, an octagon of rippling coals, like a constellation brought to ground. Something is changing in me that I can’t yet name.”

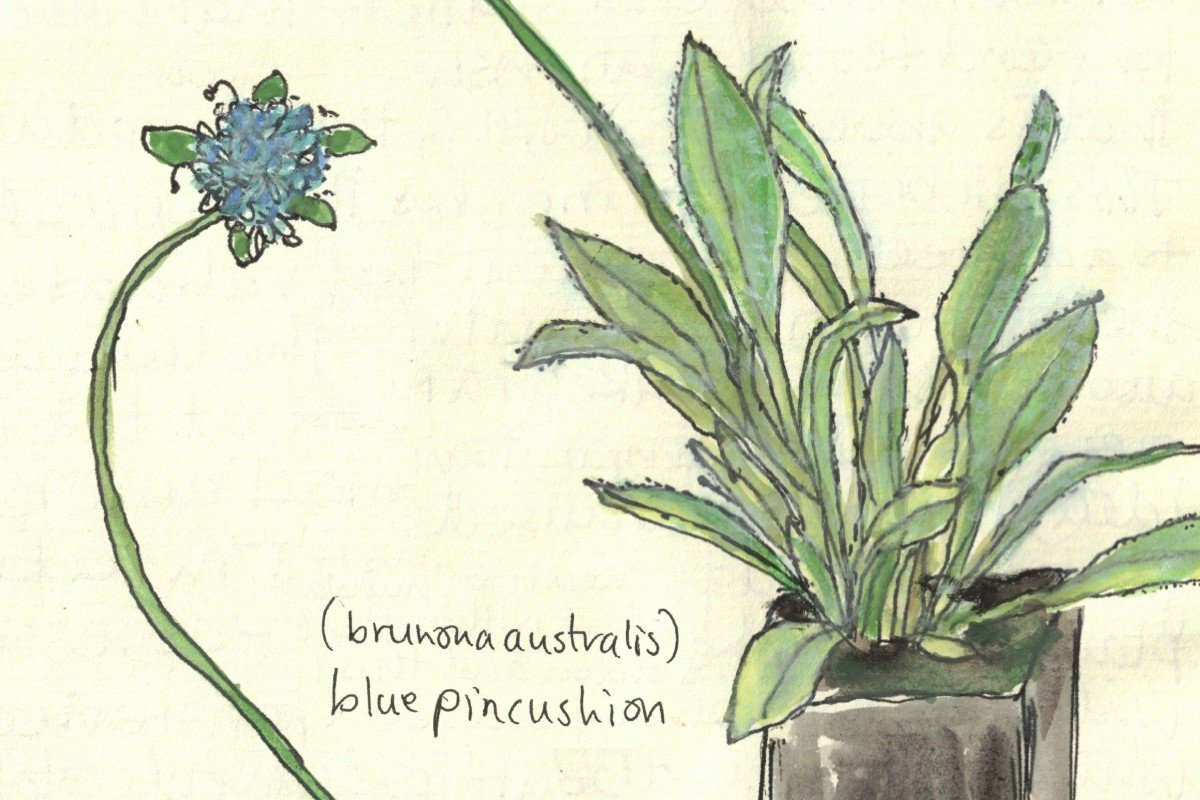

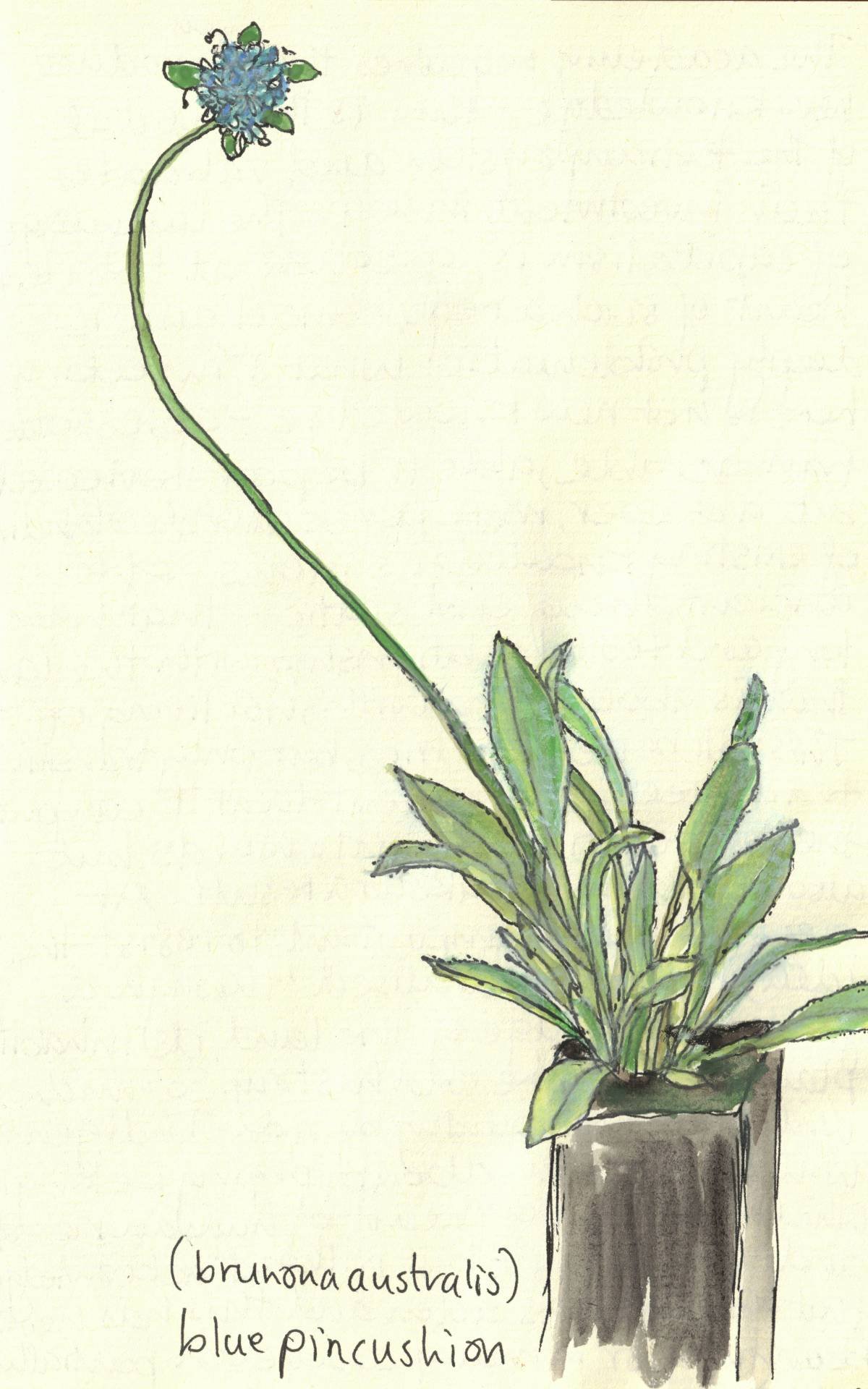

blue pincushion

Today I opt for beauty over nourishment: the blue pincushion. It sits on my table, the only flower head twisted towards the light. Beside it, a book about Fred Williams, one of Australia’s most revered non-Indigenous painters of the land. Williams lived about 500 metres from here as the raven flies; his Upwey landscapes, completed in the 1960s and a key part of his oeuvre, were often painted looking up towards the hill from where the fires would come in February 1968. Our place is on that hillside, but there’s no representation of houses in his vast landscapes or the density of bush that’s here today. In July 1970, he wrote in his diary: ‘I only use the subject matter as an excuse to hang the picture on’. As understandable as this is (I too have been enamoured with form) and as stunning as his pictures are, I’m troubled by this negation of the specificity of place. After the ’68 bushfires, he captured the regeneration of the bush on the hills around him (our house, like his, was spared). The paintings feel personal and moving; they are Williams’s own vision of the land around here, denuded, apocalyptic, smoke still rising from charred stumps. Cooking lunch, I get lost in smoke-drawing. The wind directs it, fluid and unceasing ribbons of white from the end of my fire-stick, sometimes so thick you can’t see the land or sky behind. The word comes to me – ‘calligraphic’ – used to describe Williams’s work, and an Upwey painting: ‘Landscape with Burning Tree’. In that painting, oil on canvas, a little more than a metre by a metre, I saw the same language as I do now in the smoke-drawings. Maybe it emanates from the same wood, a eucalypt regenerated on our place after the fire, or a sister tree. So much is possible within the genealogy of trees.

In my journal I paint a gumleaf that spun down from the sky; the leaf’s parchment has been scribbled on by other authors – insects, weather, time. I wish I knew their logic or how they escaped it, one tracing at a time. I wish I was five again and everything was as easy as: just give it all back.

“I wish I was five again and everything was as easy as: just give it all back.”

balm mint-bush

It’s my last full day. Two wedge-tailed eagles just flew over. I knew to look up for them because I heard the warning call of other birds that followed the eagles in a relay as they passed over different territories. Even now, when I can no longer see them, I can locate their direction by the sounds of other birds.

Tonight, I’ll leave a note by the front door inviting my humans for breakfast in the morning. It will have been seven days and seven nights. Seven indigenous species planted; so many invasive ones removed. Two bird varieties I’d never seen here before: the eastern rosella and the grey fantail. The theatre and companionship of fire. Skills learned and remembered. Pushing through an idea, testing it with the body, with time, in the company of birds. I decided to do this backyard experiment because I thought that if I’m to have any hope of understanding what it means to live on stolen land, it’s important to investigate my relationship with the portion I own, because it’s through this ownership that I’m most implicated. A week is a short time – neither the beginning nor the end. I’m still working through what I experienced; it may take years. Though I remain unsettled on this land, I understand more bodily now that it’s not belonging I seek, but meaningful coexistence in a place that embraces the truth of its colonial past and present, and justice for its First Nations peoples. And as we work towards this, a better way of caring for and celebrating this beautiful half-acre – and beyond – with which I’ll briefly live.

Land is soil, the layer of the Earth where we live and grow the things that sustain us. But it is also the story we apply to it, in all its variations; the story it applies to us; it’s what some women crave as food when pregnant, and where many of us will end when we die, interred or scattered; it gets under your nails; it’s legislated, bought, sold, bartered, and stolen; and here it was never ceded. ▼

All images courtesy of the author

This work is part of our Australian Nature Writing Project suite.

If you liked this piece, please share it. And please consider donating or subscribing so that we can keep supporting writers and artists.